Why the Everett Interpretation of QM Is Not Insane

The dollar-store version of Sean Carroll

A little over a month ago, I made a trip to Oslo to speak at the Entangled Visions workshop put on by the Quantum Hub there. I wrote a little bit about the experience of the conference, but didn’t go into all that much detail about my own talk. I’ve had a shitty couple of days, though, and writing about that seems like more fun than any of the other things I might do right at the moment, so let’s take a crack at that.

The person who invited me specifically mentioned a talk I gave a number of years ago about quantum in fiction, so I took that as a starting point. I had a shorter time slot, though, so pared it down a bit to focus on the Everett Interpretation, more commonly known as the Many-Worlds Interpretation1. Since this was a slightly more technical audience, though, I bumped the level up very slightly. I won’t do a beat-by-beat recap of the actual talk, though, and will instead try to give the general flavor of the pitch.

As I said when writing about the conference in general, I was mildly surprised to find that Many-Worlds was coolly received by the more artsy side of the group, as I tend to think of the idea of parallel universes as a rich territory for fiction. The group at the meeting leaned much more in a Copenhagen-ish direction, though, more invested in the idea of observer-created reality. To the point of occasional disparaging comments about Many-Worlds. So I ended up doing a bit of a sales pitch to argue that the Everett approach is not, in fact, insane.

To set things up, the basic problem is the same as with every interpretation of quantum physics, namely that we have a theoretical apparatus that allows us to predict the probability of various experimental results, but does not offer a sure way to predict the outcome of any one individual experiment. We get spectacularly good agreement between theory and experiment in aggregate, after repeating the experiment many many times and comparing the results to calculated probability distributions, but for any individual trial we are left (educatedly) guessing.

In the standard form of quantum mechanics that everyone learns in school2, this takes the mathematical form of a wavefunction with multiple components to it— a bunch of expressions all added together— describing the system before a measurement is made. Once a measurement is made, though, we record one and only one result for that individual trial, and it’s not clear why.

That pre-measurement wavefunction is a description of the system of interest that is fundamentally indeterminate, containing all of the possible outcomes at the same time. Some people have very passionate arguments that it’s not appropriate to say that the system “really is” in all of these states at once, but I think that’s more useful than misleading in that we can do experiments that demonstrate the presence of these different possibilities. Specifically, we can do interference experiments, where a single system is split and then recombined in a way that shows wave-like behavior.

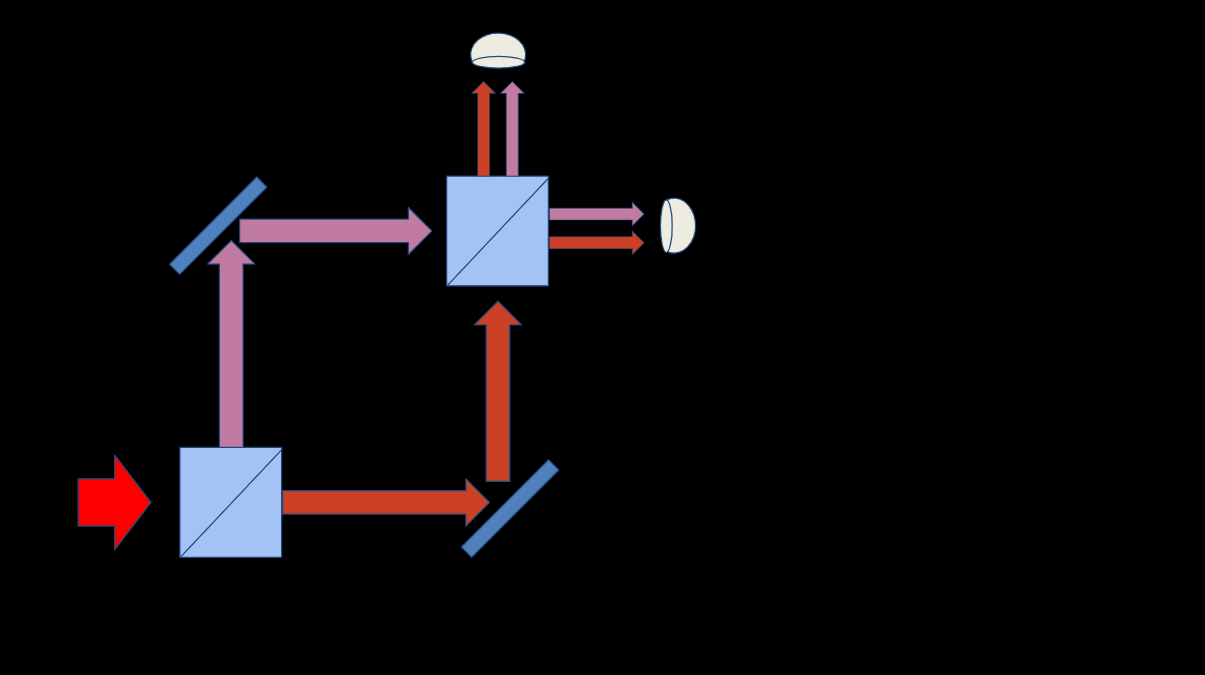

It’s useful to have a concrete example in mind for this, and one that I like because it limits the possibilities in a clean way is the Mach-Zehnder Interferometer, which looks like this:

An initial beam (big red arrow) of quantum particles— photons from a laser, or a steady stream of electrons, atoms, or molecules— arrives at a beamsplitter (blue square) that allows half of the particles to go straight through and reflects the other half at a 90 degree angle. These two different paths are steered back together with mirrors, arriving at a second beamsplitter where each is again split in half, with the output beams sent to two separate detectors.

If these quantum objects, whatever they are, behave like classical particles, we would expect that after many particles are sent through this contraption, each detector should record about 50% of them. There are four possible paths, two leading to each detector: the top detector gets particles that were reflected at both beamsplitters and particles that were transmitted through both beamsplitters, while the detector on the right gets particles that were first reflected and then transmitted and particles that were first transmitted and then reflected. Each of these paths accounts for 25% of the input particles (give or take) so each detector racks up half of the total.

If these quantum objects behave in a wave-like manner, though, the outcome depends on whether the peaks of the wave from one path to a given detector fall atop the peaks from the other path, in which case the probability of seeing the objects arrive at that detector is higher. If the peaks of the wave from one path to a given detector are slightly delayed, though, and fill in the valleys of the wave from the other path, the probability of seeing the objects arrive at that detector is lower. If you dig into the details of the operation, you find that the reflected wave is always slightly delayed relative to the transmitted, in such a way that if the lengths of the two paths are perfectly identical, 100% of the quantum objects sent into the interferometer should be detected at the detector on the right, and none at all at the detector on the top.

If you could set this up in a way that was guaranteed to be perfect, this would give you an unambiguous way to distinguish particle behavior from wave behavior— waves show up only on the right, while particles can turn up at the top. In practice, that’s very difficult to do, so instead the general practice is to scan the interferometer— moving one of the mirrors back and forth to make one of the two paths longer or shorter. Changing that length delays the waves along that path, flipping the probability for the two detectors from 100-0 to 0-100 and back again; these “interference fringes” are the signature of wave behavior. If you repeat the experiment many many times at various lengths, you’ll see the probability for each detector change smoothly from 100% to 0% and back to 100% for every wavelength you add.

Classical particles, on the other hand, don’t care about the relative length of the paths, just the probability of reflection at each beamsplitter. They’ll split 50-50 between the two detectors regardless of what you do with the lengths, so repeating the experiment many many times at different lengths just gets you two straight lines.

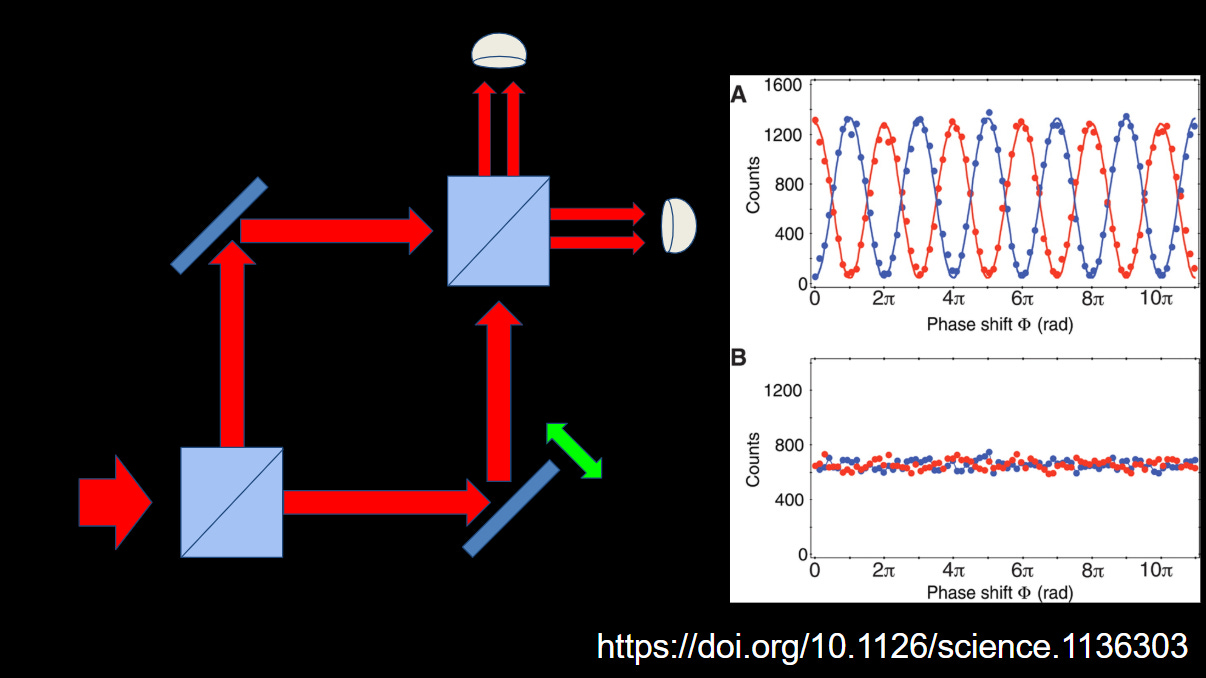

And this is, in fact, what we see, as seen in the graph pasted into the second image. For a situation in which both paths are allowed to behave in a wave-like manner (A), you see two oscillating probability curves; if you force the quantum object into only particle-like behavior by doing something to tag which path it took (changing the polarization for light, or the internal state of a material particle), you get two flat lines.

The interference pattern only exists when both paths are open and unobserved, which we tend to shorthand as “the quantum object takes both paths at the same time.” The mathematical description of the detection system will include two terms for each detector, corresponding to each of the possible paths. From this, you can determine the probability of detection for each of the two paths.

The fundamental problem of quantum measurement is that after the detectors do their thing, we end up with only one result. We record the detection of one particle at the top or one particle on the right, but never one at each. And the question is why?

There are lots of stories we can tell about what “really” happens during the detection, one broad class of which involve some kind of physical change in the system that causes the mathematical description to “collapse” from multiple terms down to a single definite answer. The details vary a lot, but all of them amount to the act of observation creating the one specific reality that we observe.

An alternative approach is to say that nothing ever collapses— that everything just stays in a superposition of all possible outcomes, forever and ever3. In this view, first laid out in the Ph.D. thesis of Hugh Everett III, the reason we only see a single outcome is that we, as observers of the experiment, get pulled into the superposition.

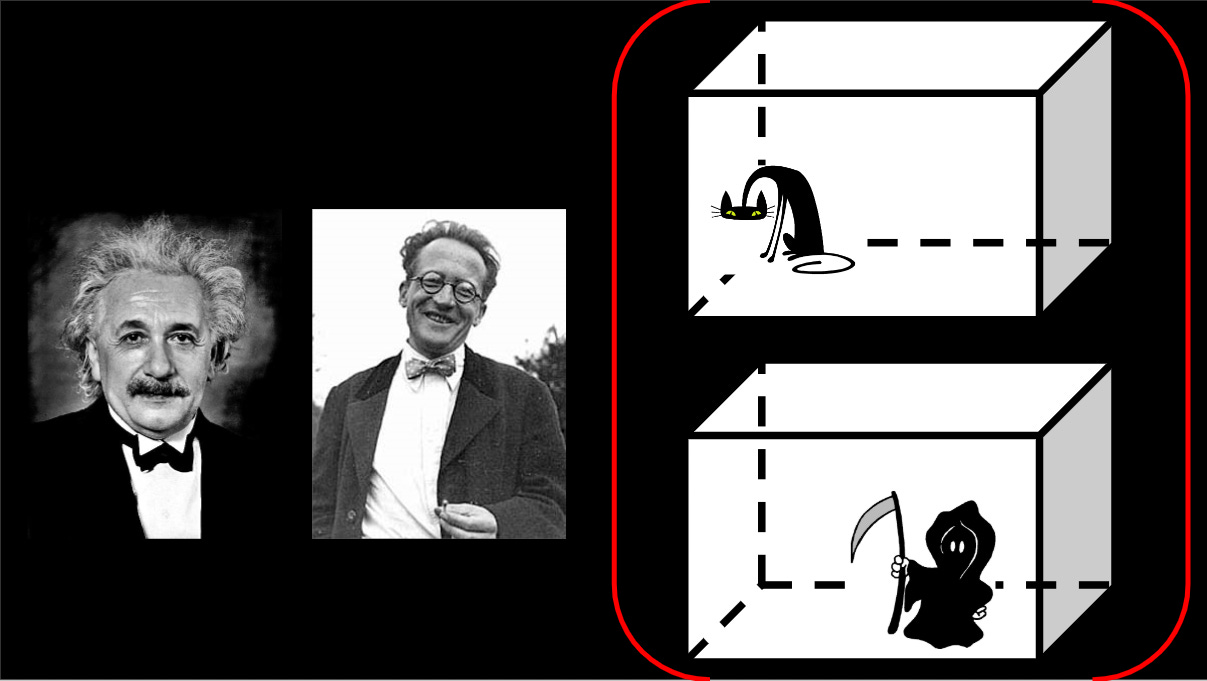

The colorful illustration I use for this is the infamous Schrödinger cat thought experiment, where a cat is shut up in a box with a diabolical apparatus that has a 50% chance of killing the cat. Mathematically we describe this as a wavefunction for the cat with two terms: one where the cat is alive, and one where it is dead. Professor Schrödinger outside the box and his buddy Albert waiting to hear the results, on the other hand, get one term each.

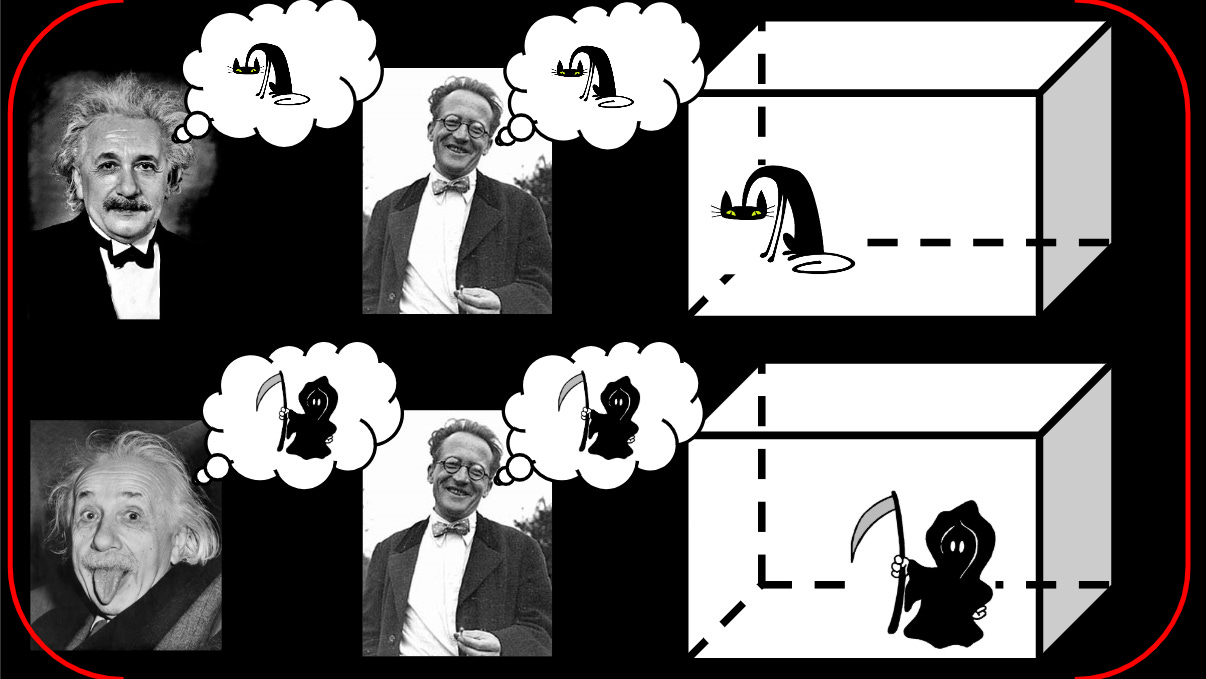

In this view, the opening of the box doesn’t change the state of the cat; instead it changes the state of Professor Schrödinger, who moves from a unified condition of blissful ignorance regarding the cat to a superposition of “knowing that the cat is dead” and “knowing that the cat is alive.” There are still two terms in the mathematical description: one with a dead cat and a mournful physicist, the other where they’re both alive and well. In technical terms, these are entangled— dead-cat and sad-Schrödinger always go together, and live-cat and happy-Schrödinger always go together, and you never get them crossed up.

Albert, on the other hand, still exists in only one state, until he hears about the outcome from Professor Schrödinger, at which point he joins the entangled superposition: there’s a live-cat-happy-Schrödinger-happy-Einstein term and a dead-cat-sad-Schrödinger-sad-Einstein term. And so on. The superposition persists forever, getting more and more complicated as time goes on.

These different branches in the wavefunction are what get called the “many worlds” that give the DeWitt brand of this view its name: you have a “world” in which the cat is definitely dead and everything proceeds from there, and another “world” in which the cat is definitely alive. This is also where a lot of people check out from the interpretation, because it seems awfully baroque to create a whole new copy of the universe for every time a coin-flip experiment is done.

Note, however, that the actual Everett approach does not require making physical copies of everything. You don’t end up with two Schrödingers because you opened the box; there’s still only one Schrödinger, he’s just in an entangled state. That objection to the Everett approach is over-indexing on a metaphor: the measurement process doesn’t create new universes, it just complicates the one we have. Treating each branch of the wavefunction as a separate universe with only one result is just a matter of mathematical convenience— once we’ve seen the dead cat, it would be annoying to continue to carry the live-cat term around in calculations, so we drop it. It’s still out there, but we don’t need to worry about it any more, so we don’t.

The next objection that tends to get raised is that it feels arbitrary to separate the branches of the wavefunction out in some cases but not in others. The Everett approach seems to require an assertion that these branches are isolated from one another in a way that doesn’t seem a whole lot less magical than asserting that measurement induces some physical collapse.

That’s also not a really strong objection, but the reason here is a bit more subtle. It’s not that the branches are forbidden to affect one another, it’s that it’s completely impractical to detect their influence.

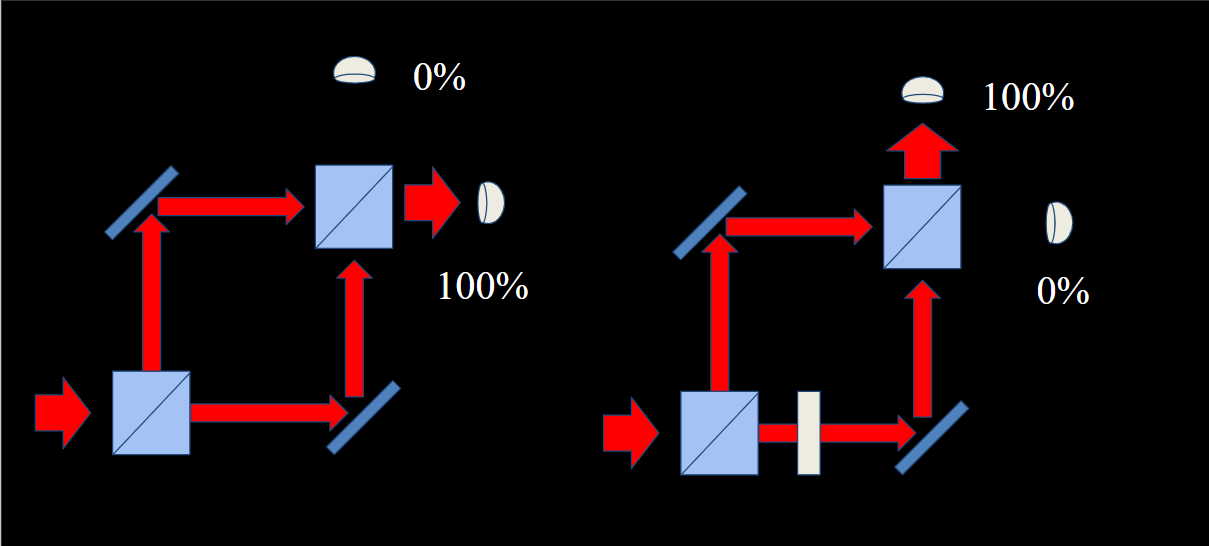

To understand why, it’s useful to go back to the Mach-Zehnder case, with a small tweak: we imagine inserting some element in one of the two paths4 to delay those objects in a way that perfectly flips the probability for the two detectors:

If we repeat this experiment many many times keeping track of whether the extra element is in or not, we will see clear and unambiguous results, both of which are entirely wave-like: 100% at the top detector when it’s in, 100% on the right if it’s out. These are unquestionably behaving like waves, just with a shift between them.

On the other hand, if we make a bunch of measurements where the extra element is inserted or removed at random, and don’t keep track of it, what we would see will look like particle behavior: 50% of the time we’ll record a detection at the top, and 50% of the time we’ll record a detection on the right. This doesn’t mean that the wave behavior has been destroyed— on the contrary, the result would be impossible without wave behavior— but it’s obscured by our lack of knowledge and control over the conditions of the experiment.

We’re able to see the wave nature of a quantum object going through a Mach-Zehnder interferometer provided we can isolate it from the environment well enough to know that there isn’t some subtle effect coming into play that might be shifting the probabilities around. The bigger and more complicated the system, the harder it is to control—in the Mach-Zehnder sort of system, you only need to move things by a fraction of a wavelength to throw the probabilities off, and the wavelength gets smaller as the mass gets bigger. Plus, the mor complicated an object gets, the more options there are for changing the internal state in a way that would preclude interference.

There’s a guy in Austria who’s made a very nice career out of demonstrating interference phenomena with larger and larger molecules. The lengths they have to go to to filter out unwanted perturbations from the larger environment are really something.

And that’s what separates the branches of the wavefunction into “different worlds” in the Everett approach. If we wanted to prove that the cat in the box is in a superposition of “alive” and “dead,” we would need to do an interference type experiment: separating the two states and bringing them back together in such a way that the probability of a particular outcome depends on having both branches there. We’d need to pull some kind of trick to make the wavefunctions associated with the cat add together in such a way that the probabilities changed by a measurable amount— that one set of conditions gives a 100% of finding a live cat, while a small tweak gives a 100% chance of finding a dead cat.

For something as big as a cat, though, this is ridiculously impractical. The level of control you would need to have to ensure consistent results through enough repetitions of the experiment to establish probabilities boggles the mind5. And in the absence of an experiment that can demonstrate the existence of other branches of the wavefunction by demonstrating some kind of interference-like phenomenon, you might as well treat the branches as separate, because it makes all the math easier.

Those are the big components of the pitch for why the Everett interpretation (and variants thereof; as with everything in quantum foundations there are about as many versions of this as there are people who have thought carefully about it) is not completely insane. There’s a third category of objection, that’s way more technical, having to do with how you arrive at the rule for determining probabilities in this approach. This shows up in versions ranging from “subtle” to “silly,” but I don’t find any of them all that compelling as an objection. The same basic problem afflicts every version of quantum mechanics— the “Born Rule” for calculating probabilities is always more imposed than derived, so I don’t know that Everett-ish approaches are all that much worse off than any of the others.

My actual talk had some other stuff in it— fiction recommendations, ad-libbed jokes, etc.— but this has gone on pretty long, so I’ll stop here. I should probably note that I’m not a deeply committed partisan of Everettianism— for that you want the actual Sean Carroll, not my dollar-store version. I remain a bit agnostic on the whole question of quantum interpretations, just because of the lack of a way to distinguish between them. A lot of the anti-Everett arguments I run into seem pretty specious to me, though, and having had to dig into this stuff for the talking dog book way back in the day, I feel compelled to push back on them a bit when the opportunity presents itself.

As always, I suspect I could run up the ol’ “paid subscriber” count quite a bit if I decided to adopt a really evangelical stance in favor of some quantum interpretation and bang on about it constantly. I’m not really wired that way, though. But if you would like to support my particular brand of squishy moderation, you do have the option of clicking this button:

And if you want to berate me for my disturbing lack of faith, the comments will be open:

A metaphorical phrasing that I believe originates with Bryce DeWitt, not Hugh Everett who came up with the original approach.

Or at least ought to learn in school…

Amen, he adds out of vestigial Catholicism.

If you’re dealing with light, a piece of glass of the right thickness will do the job; for atoms a magnetic or electric field would work.

To say nothing of the ethics review paperwork to use that number of cats…

Please - squish on. It’s appreciated.

And thank you for the most lucid description of Everettian QM I’ve read!

An excellent description of Everettian QM!

Your description of the interpretation in your book, "How To Teach Quantum Physics To Your Dog," was the first one I encountered that didn't lead with multiverse language, that instead approached it in the sense of an austere version of quantum mechanics. It was the first time the idea didn't seem hopelessly outlandish. (You also have the best non-technical description of decoherence I've seen!)

Since then, I've also encountered Jeffrey Barrett's SEP article on Everettian QM. He uses a phrase I like: "pure wave mechanics", which seems like a good way to convey the core idea. The worlds may or may not ever be testable, but pure wave mechanics is and has been.