On Quantum Foundations

Today in "Evergreen Post Topics"

Another big gap in posting from me, because this past weekend I was back at my graduate alma mater for a reboot of the Schrödinger Sessions workshop that we first did about ten years ago, now. This is a two-and-a-half-day “crash course” on quantum physics, complete with tours of some of the labs at the Joint Quantum Institute. The original rounds were targeted to science fiction writers (in the hopes of doing some indirect outreach by informing and inspiring new stories); this time out, we were going more for communications professionals: journalists and public relations folks for universities and research institutes.

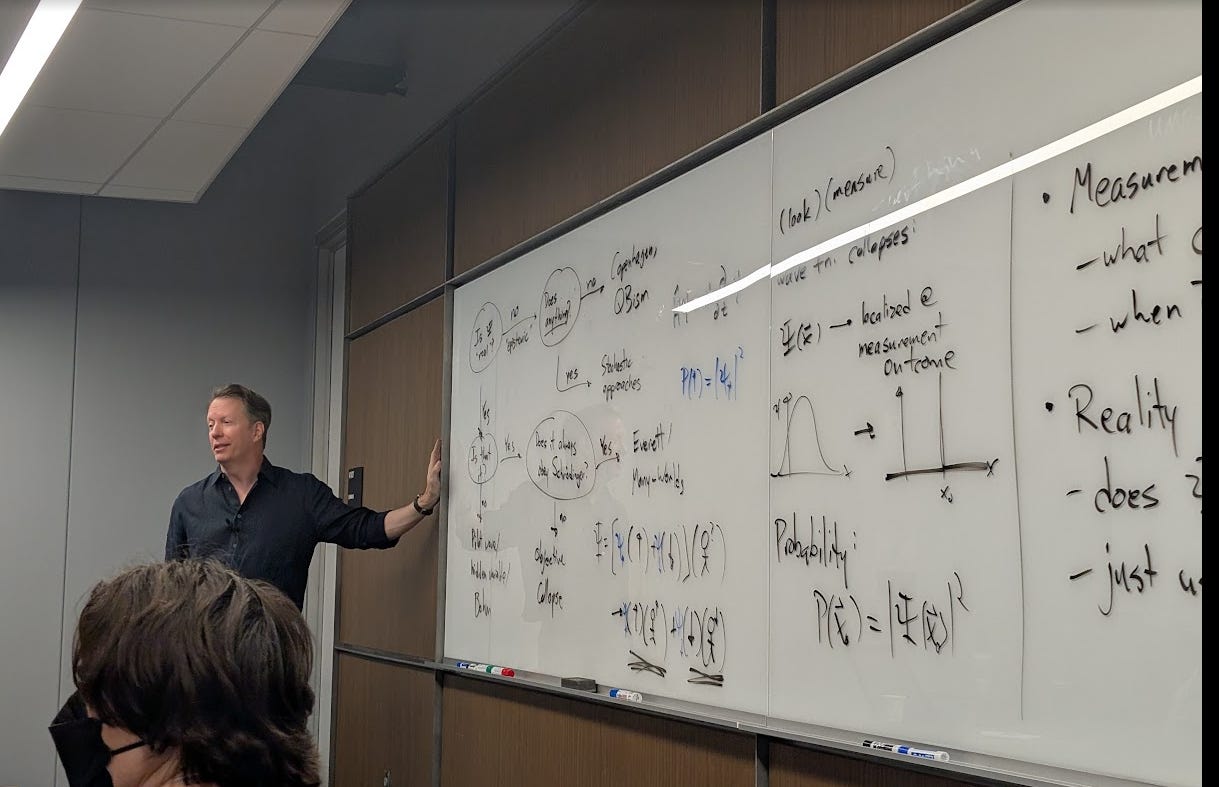

We had around 30 attendees and ten speakers for a full day of talks Thursday, some talks and panel discussions on Friday, and a round of lab tours, with coffee breaks and meals covered thanks to a grant from the American Physical Society’s Innovation Fund. Saturday morning, we invited Sean Carroll down from Johns Hopkins to talk about quantum foundations and answer very general questions from the group.

This was, as you would expect, outstanding, because Carroll is a terrific speaker and good on his feet. He did a really nice job describing the difference between classical and quantum physics and laying out the essence of the problem quantum foundations research is attempting to solve. I particularly liked the flow-chart style of explaining the difference between the options, and may steal (a version of) it for future use, which if you think about it is probably the highest praise I can offer.

This also reminded me that quantum foundations is maybe the most evergreen topic in physics blogging. When I was posting regularly at Forbes, I grumbled that I could do numbers effortlessly by throwing up a new “Your Favorite Quantum Interpretation Sucks” post every week, but that it was frustratingly difficult to get traction for any of the stuff I put actual effort into. That tipped into a sort of deliberate avoidance of the subject, which has continued for a good while now. Carroll’s talk provides a bit of impetus to shake off the accumulated layers of sediment and write a bit about it again.

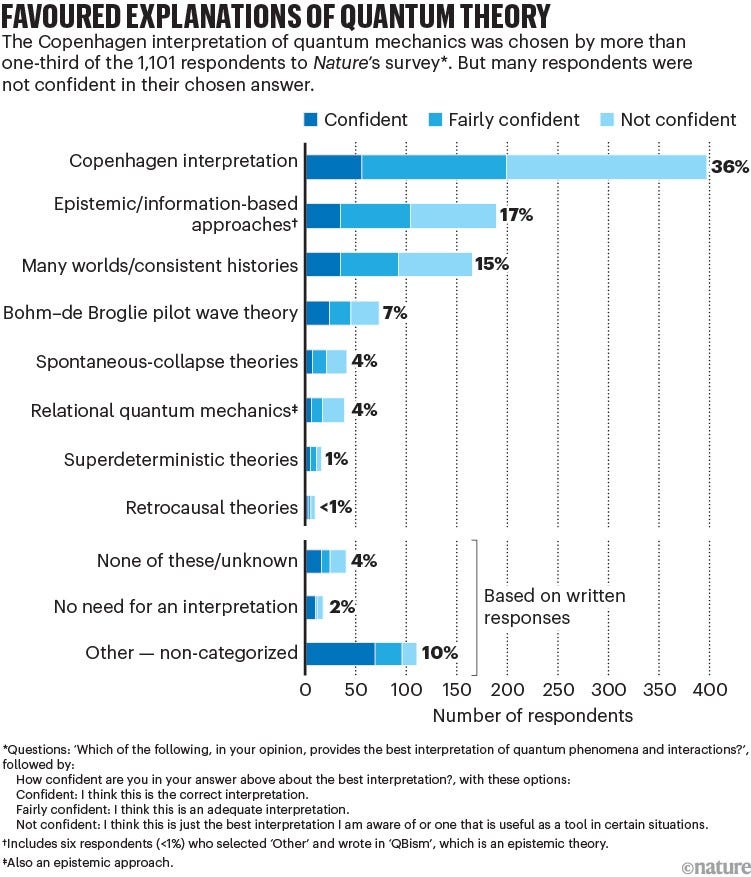

Conveniently for the workshop (but entirely coincidentally), Nature came out with a story the day before we kicked off with the (partial) headline Physicists disagree wildly on what quantum mechanics says about reality, which is highlighted by this graph of survey results:

Carroll used this to frame a lot of his talk, saying it was an embarrassing state of affairs for physics that we don’t have any kind of consensus as to what the cornerstone of modern fundamental physics really means. He noted that not only is there no single theory approaching majority support, the main interpretations have extremely soft support— barely half of the physicists choosing a given interpretation as “the best” said they were even “fairly confident” in their choice.

The winner, to the extent that there is a winner in a non-binding opinion poll, is the “Copenhagen Interpretation,” though I suspect that the combination of “Copenhagen” and “not confident” is actually just what David Mermin dubbed the “Shut up and calculate” interpretation (which was not directly an option in the poll). The idea being that the mathematical formalism of quantum theory is sufficient to predict the outcome of experiments to any level of precision you might reasonably ask for, so you can just skip lightly past questions about the nature of reality and what constitutes a measurement. This is actually a decent fit with the core idea of Copenhagenism— Scott Aaronson’s characterization of it as “shut-up and calculate except without ever shutting up about it” is not without an element of truth.

Carroll vigorously argued for the position that the various “interpretations” of quantum theory are, in fact, more than mere meta-theories, and say very different things about the nature of the world. He laid this out in flow-chart form, as seen in the photo above, but I find it interesting to note that while he has Copenhagen as the principal endpoint of the “epistemic” branch (where the answer to “Is the wavefunction real?” is no, and so is the answer to “Is anything real?”), the survey has “epistemic/ information-based approaches” as a separate category. Which again raises the question of “What question did respondents think they were answering when they said ‘Copenhagen’?” and threatens to tip the whole business over into “Why I’m Glad I’m Not a Social Scientist” territory. If you hold to the characterization Carroll uses (which aligns with many other philosophically-inclined folks1), that would say that “epistemic” theories have a slim majority (53% give or take some rounding error), but again, very soft support.

As noted above, I like the flow chart presentation a lot, and think it does a good job of laying out the ways that the various approaches are very different. It even makes clear the handful of places where it seems like there might, in principle, be clear experimental tests— the difference between “objective collapse” theories and Everettian approaches, for example, where one group of theories would say that the Schrödinger equation breaks down on some time or length scale and the other says it continues forever, world without end. There’s also some possible room for differences with the de Broglie/ Bohm picture, where non-local potentials guide particles with well-defined properties and the probabilistic stuff comes in through some assumptions about the initial conditions that might possibly be violated.

I also tend to agree with Carroll that the different approaches to questions regarding the nature of quantum mechanics tend to shape the way physicists using them think about the questions they ask and the experiments they propose. To use an obvious example, if you favor (or strongly oppose) an objective-collapse model, that makes it extremely interesting to think about experiments that push toward the limits where you expect the collapse to be triggered. On the other hand, if you favor a de Broglie/Bohm sort of approach, you might find it especially fruitful to think about “weak measurement” experiments where you use partial information to reconstruct the underlying trajectories, and so on. This makes it useful to have people exploring the space of possibilities in quantum foundations so as to offer the greatest possible diversity in experimental approaches.

In that same spirit, though, I think there’s a very real sense in which people’s research background shapes the way they think about these issues and the importance they attach to these questions. Carroll noted that the philosophers he talks to tend to be inclined toward de Broglie/ Bohm models because they’re very concrete, but he personally doesn’t think much of them because they have issues when it comes to applying them to fields. But to some extent that’s a function of his background in cosmology and high-energy physics, where quantum field theory is the coin of the realm.

This was most clear in a bit of back-and-forth between Carroll and my Ph.D. supervisor Steve Rolston (then at NIST, now at UMD), who is a cold-atom guy by profession. That low-energy experimental context is probably the quantum-adjacent area in which the questions of quantum foundations matter the least, and a “shut up and calculate” approach is most practical and appropriate. There are any number of experiments you can do in quantum optics that don’t pose any significant problems for a Copenhagen-ish “quantum theory makes predictions about the outcomes of experimental measurements” approach to the day-to-day business of doing physics. Vast swathes of condensed matter physics are in the same category, on up into biophysics and materials science, likely accounting for a significant majority of the people who have “physicist” in their job title.

I don’t entirely agree with this with regard to low-energy experimental quantum optics— elucidating weird quantum phenomena has long been a big push in the field, including ongoing efforts to scale up to large quantum computers, and I think those definitely do raise questions of interpretation. See, for example, things like our former NIST colleague Aephraim Steinberg’s work on things like quantum tunneling and the propagation of light in a medium, where there are major arguments about whether it’s even appropriate to assign a position to an atom going through a barrier. I do think Rolston has a point when it comes to the overall weighting, though, in that Carroll is coming at this from a background in cosmology and high-energy theory, subfields that are infamously rife with intractable problems. They’re not lacking for experimental data, exactly— on the contrary, there’s probably more actual quantitative data relating to questions about cosmology than ever before— but none of the data allows a clean distinction between theoretical alternatives. Which is the kind of scenario that might very reasonably lead one to conclude that there’s a very deep problem with the overall program that requires going back to the very foundations and rethinking everything.

I largely buy the wheel-spinning feeling in fundamental theory as a case for the importance of thinking carefully about foundations in the context of cosmology and high-energy theory. For physics as a whole, though, I’m less convinced that this is critically important. I absolutely agree that it’s a topic that should be taken seriously and accorded respect, but at the same time, if it remains a somewhat niche subfield, I think that’s probably fine. I don’t think we need to be making it a top priority to push huge numbers of graduate students toward quantum foundations research, or anything2.

Which, to some degree mirrors an answer Carroll gave to a question about public outreach during the more AMA-ish portion of his session, which is the same answer I give when I get asked about whether physicists should be pushed to do more public communication. We both note that speaking to a general audience requires [Liam Neeson voice] a particular set of skills [\Neeson], and that not everybody has those skills or the interest in using them. We shouldn’t be pushing people who aren’t good at or interested in public communication to put themselves out there more; instead, we should give support and recognition to those who do have the skills and interest to do that work.

In the same way, I think quantum foundations is an important and worthwhile subfield, deserving of serious thought and inquiry. At the same time, making any progress in that area requires a particular set of skills that are not uniformly distributed, so it’s not necessarily going to benefit from a massive influx of new people. What we need is just to support those who do have the skills and interests in their decision to pursue research in quantum foundations.

Happily, I do think this has improved over the last few decades, thanks in part to the rise of quantum information science as a significant subfield of physics. There’s a bit less crazy-person stigma attached to these questions than there used to be, and that’s a good thing3. There’s still work to be done, though, both in the actual shoring-up of the foundations and the respect accorded to that important work.

Anyway, it was a fun workshop and nice to get to spend some time thinking about weird and fun stuff again. And a good way to close out a busy summer of work-related travel ahead of having to think about the return of classes in a few weeks.

That got a little rambly, but it’s that kind of topic. If you want more in that vein, here’s a button:

And if you take issue with any of this, the comments will be open:

Though not all, because philosophers.

We may inadvertently be doing so, though, in a How the Hippies Saved Physics sort of way, thanks to the recent gutting of research funding in a fit of pique.

Sadly, the absolute number of crazy people associated with these questions has not gone down; they’re just a smaller percentage of the total.

On another note: any chance that Sean Carroll's talk got taped, and is/will be available? I would love to watch that.

>>> We shouldn’t be pushing people who aren’t good at or interested in public communication to put themselves out there more; instead, we should give support and recognition to those who do have the skills and interest to do that work.

Spot on. I'd emphasize it further: I know that it has long been a problem for people interested in doing public outreach, as far as their university jobs go. I wish there was some mechanism whereby, say, writing a book for the general audience counted as much as publishing a journal paper.

Preaching to the choir here, I know, but still, hopefully others start to sing along.