Grade Inflation's Just This Thing, You Know?

Maybe a couple of things, actually...

I’ve had this piece on grade inflation by Rose Horowitch The Atlantic open in a tab for a week or so now, because I feel like I ought to write something about it. The problem is that I’m not really sure what to say.

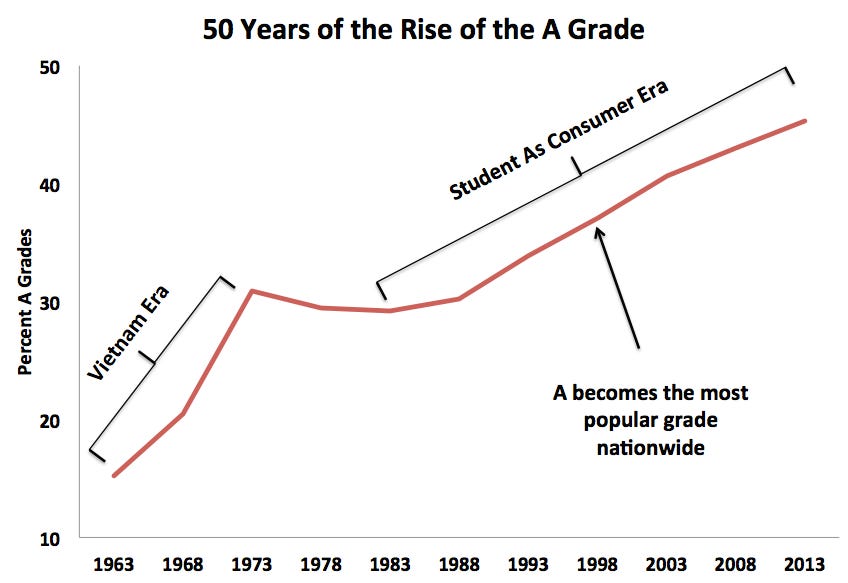

Grade inflation, that is, a steady upward creep of the average GPA at a wide range of educational institutions, is very much a real phenomenon. You can find endless variants of this basic graph online (this particular one is from gradeinflation dot com, showing the fraction of students receiving A grades in a historical database):

There are versions of this that track the corresponding decrease in grades lower down the scale— see, for example, this piece from the NYT archives— and any number of institution-specific versions— here’s one from my alma mater. On a local level I have access to much more granular data for Union that I can’t really talk about other than to say that we’re basically on the same trend: the average GPA has crept up at a rate of a tenth of a grade point per decade, give or take.

All the graphs show basically the same features— a relatively rapid jump in the number of high grades given out during the late 1960’s, then a slow upward creep since the mid-1980’s. As noted on the graph above, these are readily attributable to two different phenomena, with the rapid growth reflecting faculty and students trying to preserve draft exemptions during Vietnam. The slow growth after that is… something else.

(A quick Google search didn’t show anything that goes through the present day, but I would not be at all surprised if there’s a second upward “kink” in the line around 2020, for the COVID class. Again, that’s some combination of sympathetic faculty grading leniently during a time of crisis, and students with fewer distractions than previous classes.)

My “what to say?” problem with the Atlantic article is that there’s enough going on here to put this very solidly in the “Reasons I Am Glad I’m Not a Social Scientist” zone. The standard semi-polemical explanation is what you see in the label on the graph above: the rise of a “student as consumer” approach where faculty are pressured to give better grades to mediocre work thanks to the over-use of student surveys in faculty evaluation and promotion.

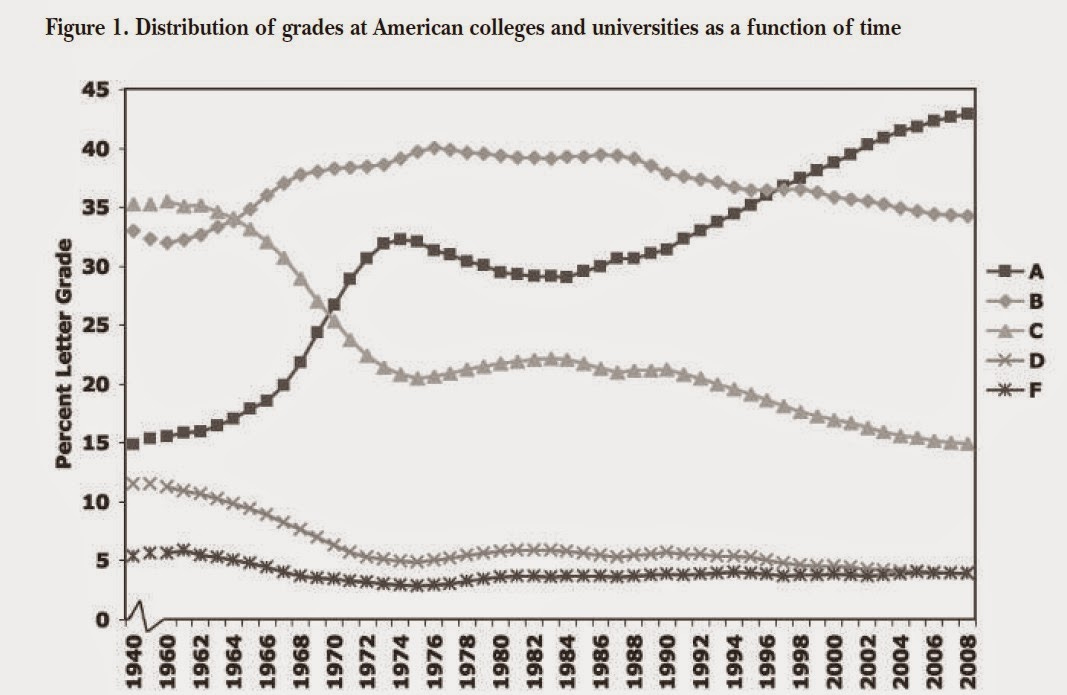

At the same time, though, there are arguments ready to hand for why that’s not the explanation, or at least not the whole explanation. For one thing, if you look at versions of the graph like the one in the NYT link above, that extend back well before the Vietnam era, you see that the slope of the “A” line in the post-Vietnam era is not that different from the pre-draft data; here’s a version from a 2104 blog post:

If you put a straightedge along the data from before 1966 or so, and imagine using it to extend the line into the 2000s, see an upward slope that’s not too different from the post-1986 trend. The Vietnam bump might’ve sped things up slightly, but the trend was there before the draft.

This reflects the fact that there was an absolutely enormous change in the population of students attending colleges and universities over those several decades. A lot of barriers relating to class, race, and gender were removed— most of the elite private colleges in the Northeast went co-ed around 1970 (give or take)— allowing a more open competition. This could plausibly result in some “authentic grade inflation”— improving the overall pool of students by replacing the lower tier of mediocre rich boys with talented women and people of races and classes who never would’ve been accepted in the 1950s1. Secondarily, there’s a kind of nationalization of the pool— back in the day most colleges and universities tended to recruit on a relatively local basis, but over the last few decades that’s much less of a factor. Colleges are casting a wider net geographically (in no small part because population has shifted away from the Northeast where the density of colleges is highest), and students are more willing to consider more distant schools than in the past. Again, this can produce some “authentic inflation” through a net increase in the talent pool— you replace some mediocre students who happen to live in the right area with better ones from farther away. There’s even some globalization at work— most colleges have substantially increased the number of international students on campus over the last few decades2, again raising GPAs by broadening the pool.

What’s the real story? I think both of these are real effects, so what you see is a mix of the two. Colleges that used to be basically finishing schools for the sons of the idle rich have refashioned themselves into serious academic institutions, with an overall improvement in the quality of the educational outcomes that might justly be rewarded by higher grades. At the same time, though, there’s a very real upward pressure on grades that’s independent of the actual learning outcomes.

I’ve just started my 25th year as a professor, and over that time the distribution of the grades I give out hasn’t really changed. At the same time, though, there are questions I put on exams a quarter-century ago that I wouldn’t dream of asking now, because nobody would get them. Some of this is a reflection of better learning on my part— I’m a bit less likely to try to get tricky with the wording of problems because I don’t want to over-weight the ability to parse colloquial English, which I was probably doing in the past. Some of it, though, honestly falls into the bad category of grade inflation.

The primary mechanism here is psychological. When I was a student, I took quite a few upper-level physics classes where the mean grade on an exam would be around 60%, which would end up as a B on the transcript, so we were more or less willing to roll with it. That just does not fly any more— if the mean grade drops below about 80%, students start freaking out, and won’t be reassured by explanations that the conversion from percentage to letter grades is not a strict linear mapping. So when I sit down to write a new exam, consciously I’m trying to target a higher mean score than I would’ve in the past, even if that means losing some resolution on the top end, just to reduce the number of students freaking out in my office. I think a “B” grade still corresponds to approximately the same level of mastery of the relevant material, and we’re just not doing as much to separate the A+ students from the A students, but I can’t be confident in that because it’s not possible to tell with the current tests3.

So it’s all a bit of a muddle. There’s good along with the bad, but they’re hard to tease apart. And I don’t really know what, if anything, can be done about it— a lot of the obvious measures you might use to try to mitigate this have weird effects, as related in the Atlantic piece and in more detail in the econ blog post. Which boils down, in the end, to “I’m Glad I’m Not a Social Scientist.”

The other reason I’m a little hesitant about how to react to the original Atlantic piece is that like most American writing about higher education, it’s 1) highly anecdotal, and 2) all the anecdotes are about Harvard and Yale. I’m not sure I believe that the shift to a “shadow system of distinction” based on extracurriculars is a general phenomenon as opposed to a specific pathology of Harvard and Yale4.

Related to that, and also in the “Glad I’m Not a Social Scientist” bucket is how heavily this stuff relies on various levels of self-reporting, which I suspect is highly susceptible to a kind of social desirability bias. That is, the primary indicator of the pernicious effects of grade inflation and extracurriculars is an increase in students who report feeling stressed out or who seek help for feeling stressed out. But over the span of a few decades, there’s been an enormous increase in the acceptability of those things. There are even big swathes of the social Internet where loudly declaring how stressed you are is de rigueur, and having particular kinds of crises is its own kind of shadow status indicator.

I definitely remember feeling stressed and anxious at a variety of points in college and grad school, but at the time it would’ve been nearly unthinkable to admit that to anyone beyond a really close circle of friends. We tended to try to power through and/or self-medicate with a variety of substances5. I’m not sure how you tease apart how much of the stuff in the article reflects a genuinely problematic change in the conditions for students from just an overall increase in the willingness of students to admit to problems that were there all along6.

So, again, it’s all a big muddle, and I don’t know what you do with or about it. Other than offer quiet gratitude for not needing being a social scientist who has to deal with this kind of stuff on a regular basis.

I wish I had more of a grand, sweeping policy proposal to pitch here, not least because then I could tap into some sweet, sweet lecture-circuit cash. If you’d like to see whether I come up with anything lucrative down the road, here’s a button:

And if you’d like to suggest anything along those lines, or just yell at the clouds about Kids These Days, the comments will be open:

My favorite anecdote along these lines: When I was at Williams, a cranky alumnus from the class of 195mumble wrote a letter to the school paper declaring that the place had gone to hell with the rise of “soft studies” departments and programs. My favorite history professor there wrote a response that was, essentially, “I was a student here at the same time as you, and you and your friends were a pack of idiots. The students I teach today would run rings around the lot of you, academically.”

At least, they were increasing until the one-two punch of COVID followed by handing the keys of the immigration system over to creepy dead-eyed trolls.

Changing to an assessment system without obvious percentages might seem like a way around this, but when I’ve tried it it mostly leads to a lot of students asking for letter-grade conversions on a weekly basis.

And even more specifically about Harvard and Yale students heading for careers in finance, who are a very particular breed of sociopaths.

One of my favorite rejoinders to someone only slightly older than me declaring that “Back in my day, we didn’t have ‘Adult ADHD’…” was a doctor saying “That’s because everyone smoked all the time, and nicotine is accidentally pretty effective as an anti-ADHD treatment.”

Which might net out to a Good Thing overall, to the extent that this greater willingness to share anxiety leads to more effective treatment of those pre-existing issues than previous generations got.

A moderately long story on grades and grade inflation…

When I was an undergrad, back around 1990 or so, I didn’t like the system of grading where if you happen to bung up a big exam (say, your midterm worth 30% of your overall grade), it would be mathematically impossible to get an “A”, a somewhat dispiriting situation to be in for the remainder of the term.

The professor who I complained about this to suggested I come up with an alternative, which I did (and which we then implemented over the next four semesters, as he recruited me as a TA…)

Basically, there would be 1300 “units of work” over the course of the semester. Your final grade would be the mean of the highest 1000 “units of work”. In this way, if you wanted to skip a particular exam, or really, really, liked projects, or didn’t want to do homework, you could do that, so long as you did 1000 units of work. If you were a little desperate and willing to work hard, you could ask for an additional project (worth, say 200 units) - and if it was “A” quality work, it would knock off 200 units of “F” quality work that was the mid-term you bombed.

We found it really improved student satisfaction, while still requiring “A” work to actually get an “A”. It motivated students to improve rather than give up, and gave multiple paths to do well. Excellent students liked it, because if they aced the entire class and did every assignment, they could skip the final… or take it, with no jeopardy to their grade, as they already had 1000 units of “A” work. Several, in fact, did just that, because they wanted to see how well they’d do.

(And I got to learn the joys of scripting a now ancient piece of software, Lotus-123, to actually calculate those grades. Backslashes galore.)

But… it also made it easier to mark bad work as bad, because you knew you were giving the student many opportunities to improve. And maybe that’s part of tamping down grade inflation, because if you have the sense that you’re really harming a student by giving them a bad grade… you’re going to be less likely to do so.

To me, the funny thing is that once you get your first job or get into grad school, nobody gives a rat's ass about your GPA.