Last week, there was Yet Another Tweet in one of the academic-social-media genres most likely to make me become the Joker, namely decrying the existence of “weedout courses” in the STEM disciplines. I can’t be bothered to sift through ex-Twitter to find the specific example, but it comes up regularly enough that I’ve written about it at least twice in the time I’ve been running this Substack (big embedded-post tiles here just to see if that makes people any more likely to click through…); the TL;DR version of why this drives me nuts is that non-STEM people often look at this like something scientists do specifically to be exclusionary and dickish, when in fact it’s just a reflection of the hierarchical nature of the disciplines.

A Limited Defense of Weed-Out Classes

Via Matt “Dean Dad” Reed, I read this Washington Monthly piece on a study of wage gaps for different undergraduate majors. Specifically, it’s looking at a study from the University of Texas system that showed the usual large racial gap in pay within STEM and business majors, but

Every Class Is Some Student's Orgo

The big topic of the week was the non-renewal of Maitland Jones as an instructor at NYU after students in his organic chemistry class complained to the administration that they felt their grades were too low for the effort they were putting in. This was aptly described by Ian Bogost on Twitter as a “grenade of shibboleths:”

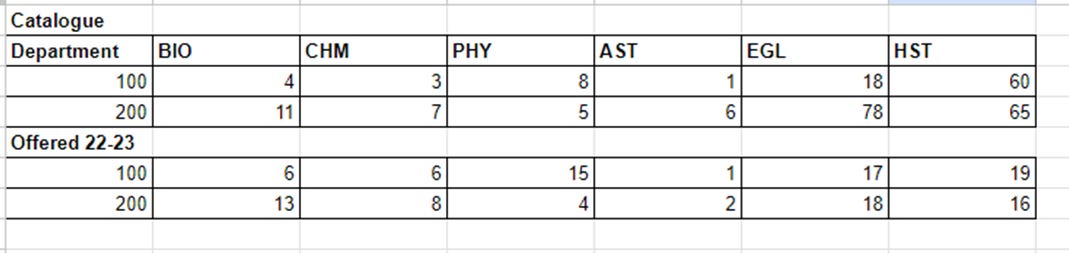

I was solo parenting at the end of last week, so didn’t have the spare processing cycles to write about it then, but in the process of doing some student advising it occurred to me that there is a moderately quantitative way to make clear the nature of the difference I’m talking about. So I did a quick-and-dirty version of that this morning while killing time before a meeting.

The methodology is pretty straightforward: I went through our online course catalogue and counted up the number of courses listed at the 100- and 200- levels, which generally count as entry points for the respective majors. I did this for three representative science departments (we’re both Physics and Astronomy, though I broke the courses out separately below), and English and History as examples of not-STEM fields. The results are in the first group in the table below:

The average number of intro courses listed for the science departments is about five, compared to 18 for English and 60 for History. Physics stands out as having the largest variety of intro classes because we offer two different flavors of introductory calculus-based physics (we do a team-taught version with Math that does calculus alongside the physics), plus the “Physics for Pre-Meds” classes that have numbers in the 100s but almost never feed into the major track. At the intermediate level, the number of offerings increases for the sciences— mean a bit more than nine— but is something like eight times that in English and History.

These are course numbers listed in the catalogue, so the obvious objection here is that a bunch of those English and History courses are one-offs or defunct courses that haven’t been offered in years. Which is why there’s the second group, showing courses listed as having run in the 2022-2023 academic year (because I accidentally selected a term from that year rather than this one, and decided to just roll with it). This is the total number of courses offered at the relevant level, so a bunch of these are duplicates— we run the two engineering sequence intro courses every term, and English does both 100 and 101 every term, so those account for six out of each of our totals (we’re on a trimester calendar). The Physics total is also goosed upward by the inclusion of four pre-med classes that, again, arguably shouldn’t count.

This illustrates what I’m talking about when I say the issue of “weedout courses” is structural: even using the raw number for physics, there are just about twice as many 100-level offerings in English and History as in the science departments, and likewise at the 200-level. This doesn’t change all that much if you attempt to account for duplicate course numbers— you can take out the “extra” sections of English 100 and 101, dropping that total down a bit, but the same is true for Biology and Chemistry, who offer the same intro courses every term, plus a couple of once-a-year honors sections. Fully half of the 200-level Chemistry offerings are Organic Chem, the quintessential example of a “weedout” class.

This is a more quantitative cut at the problem I was getting at in the second of the pieces linked above. Each and every one of these classes is, for some number of students, the class that “weeds them out” of a particular department: the one that makes them say “You know what? I don’t want to do this any more.” But owing to the inherently hierarchical structure of science majors, the number of options for what that class might be is much smaller: there are at least twice as many courses that might drive a student out of a major in English or History as there are in Chemistry or Physics. Which is a big part of why it’s so much more common to hear “I thought I was going to be a chemist until Orgo kicked my ass” than it is to hear any specific History class called out.

This is not to say that there aren’t ways to improve teaching at the introductory or intermediate levels of STEM majors— God knows, I’ve heard plenty of stories of dickish and exclusive behavior by people teaching Organic Chemistry1. But even if you could fix all of that, and make those courses as welcoming and inclusive as humanly possible, you’re still going to have more students whose last class as a Chemistry major is Orgo than you will for any course in the not-STEM major of your choice.

A better description of these classes, then, rather than “weedout courses,” might be “bottleneck courses,” because that’s a little more fair about what the actual issue is. It’s not that students are deliberately being mistreated or pushed out for shits and giggles, it’s that everybody considering one of these majors gets channeled into the same handful of introductory and intermediate courses. As a result, those become the exit point for a large fraction of the students who decide to major in something else.

I’ve had a wretched cough for the last several days, which is finally easing off enough to let me write. If you like this and want more, here’s a button:

And if you want to dispute or suggest refinements to my what-can-I-bang-out-in-half-an-hour-before-a-meeting methodology, the comments will be open:

Not at Union, of course. All my colleagues are lovely people.

I like characterizing it as a bottleneck, although I think another core problem is that we let people talk about it as if the purpose of the class is to show people that they CANNOT succeed in the major, when much more often what it's showing people is that they MUST WORK HARDER to succeed in the major. And some people respond to that by pushing through the bottleneck, and some people respond to that by moving to a degree program that doesn't include the bottleneck.

But telling someone "it's OK if you don't want to work that hard, you can pick a major that is better suited to you" comes across a lot better than "I don't think you're cut out for this."

One way to look at these, if you can get the data, might simply be DFW rates. At my university the only two "weed-out" courses in History are the two halves of the survey -- beyond that, we have distribution requirements for geography/time period, but we do not have an especially structured major beyond that. My experience is that relatively few students get actual Fs in my surveys, and only a few more get D's. But I have a number of students who simply stop showing up or never show up or only show up form one or two classes and then don't drop properly. I used to give those people a W, because I did not want to give them an F that wasn't really an F. That option is foreclosed in our latest grading input system. Whether that weeds them out because they never end up finishing (the two surveys are also a gen ed requirement for all students) is another x factor, and one that probably does not happen as much at an elite SLAC than at a state master's comprehensive.