So, last week the first part of my series on the history of laser cooling went live at Physics World. Part 2 is currently in the editing/production process, and part 3 has yet to be written.

Given the nature of these things, there was a lot of stuff that didn’t make it into the published piece. Some of these are specific anecdotes or turns of phrase, others are more general themes and common elements, and many of them may eventually see the light of day in some other form, but I thought it might be useful to highlight some of them here.

— Talking to people who were there at the very beginning is a great reminder of the sheer number of enabling technologies needed to make laser cooling experiments work, and how much that’s changed in the decades since the field started. The most obvious is, of course, the invention of the laser in the first place— all the way back in the early 1930’s, Robert Otto Frisch and Otto Hahn did experiments demonstrating light forces on atoms, but when your only source of light is a thermal lamp, it’s just next to impossible to get a significant force. Frisch’s experiment from 1933 is an impressive bit of work, the culmination of several years of tour de force atomic-beam experiments (completed just before both Frisch and Hahn were hounded out of Germany by the Nazis). It only shows a deflection of about a millimeter over a couple meters of path, though, because the light is just so weak.

The development of lasers starting in 1960 gets you enough photons to start to generate significant accelerations, which is why it starts being thought about then. The core physics needed was understood for a few decades, but nobody really looked that closely at it before then, because it just wasn’t feasible.

Beyond lasers, though, there are a bunch of other key bits of tech, most notably the vacuum side of things. Laser cooling works because atoms only absorb light in a very narrow range of frequencies, which means that the cooling only affects one species. Any other species of atoms or molecules in the area will be unaffected, and are prone to colliding with the atoms being cooled, heating them right back up. A recurring theme in the conversations I had with people about the early experiments was the need for good vacuum. If you’re in the field you just sort of take this for granted, but it’s a bit surprising even now for people in different areas.

— It was also interesting to be reminded of the rapid improvement in experimental control and data collection. I joined the Phillips group in the summer of 1993, and by that time all the experiments were being run by copies of a LabView program written by a post-doc who had some coding experience. The various beams we needed were switched on and off electronically using acousto-optic modulators and occasionally electronic shutters. We read a lot of our data into the computer directly, either as an analog voltage or a pulse-counting signal, and wrote the data files to disk.

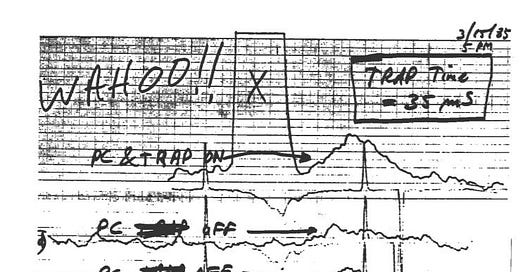

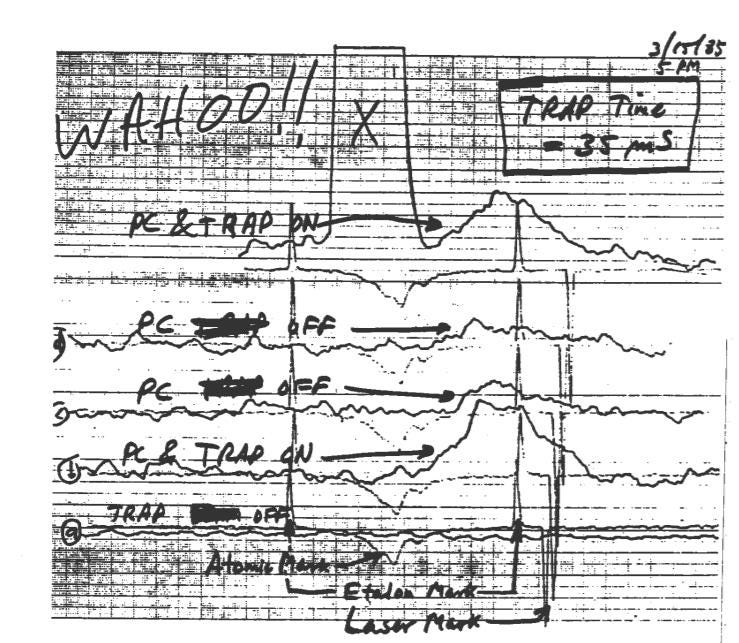

Not all that long before, though, the first trapping experiments took their timing off a spinning cardboard disk with holes cut in it to allow light to pass for different intervals. Non-optical parts of the experiment were synched to a light pulse from the disk, and timed either internally or using a PDP-11 microcomputer. The data showing trapping was taken using a chart recorder— Hal Metcalf famously scrawled “Wahoo!” on the paper with the key data trace.

— It’s also remarkable how everything seems to trace back to the same handful of key papers and key people. The first suggestion that light momentum can affect the motion of atoms is from the same 1917 paper by Einstein that introduced stimulated emission, which makes lasers possible. Just an absolutely pivotal moment in atomic physics, that, and one I keep having to write about (I think it’s appeared in at least three of my books). I highly recommend Dan Kleppner’s appreciation of it from Physics Today back in 2005.

There’s also a pretty tight academic family tree involved in the early days of this. Wineland was a student of Norman Ramsey’s at Harvard, as was Dan Kleppner. Phillips was a student of Kleppner’s. And if you want a pop-culture hook, Ramsey was a student of I.I. Rabi, who figures prominently in Oppenheimer.

— Another theme that came up a bunch but was hard to fit into the word count for the feature articles was the degree of freedom that the researchers launching the field were given. The whole thing was kicked off by Art Ashkin at Bell Labs during the golden age when they just turned smart people loose to study whatever they wanted. Dave Wineland and then Bill Phillips were both hired by the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology) to do specific things, but were also given the opportunity to launch new projects on laser cooling. As those started to get rolling, the NIST brass gave them a lot of room to operate— by the time I got there, Phillips had only the most tenuous connection to the original project he was hired for, and the group was entirely devoted to basic research in laser cooling.

Both Phillips and Wineland particularly cited Katharine Gebbie, who I knew as the Director of the Physics Laboratory at NIST when I was there, but who started at a somewhat lower level. She was a big proponent of “hiring smart people and staying out of their way,” which has paid off in the form of a bunch of Nobel Prizes for NIST physicists. Plus, you know, the whole “revolutionizing atomic physics” thing…

—The early community was small, and very collegial. That’s not to say that there weren’t rivalries, but the principals all knew each other, and talked with each other regularly. Some of them are more competitive than others— Ashkin’s book talks at length about how he felt slighted by various other figures, and Bob Drullinger got himself in hot water by saying “That Nobel should’ve been Dave’s” to a reporter when Chu, Cohen-Tannoudji, and Phillips won in 1997. Some of the others are remarkably generous about giving credit to other people; there’s a story in part 2 about Jean Dalibard declining a co-authorship on the first magneto-optical trap paper because while the idea was his, he wasn’t part of the experiment.

This may to some extent be the family tree thing again— as noted above, a lot of the American part of the story starts with Norman Ramsey, who was a consummate gentleman. In France, the key figures are connected to Alfred Kastler, who was also highly thought of. But it’s a bit more than that, as their are other folks from outside that network who are also much more collegial than you see in some other fields of physics. (And let’s not even talk about how people in the life sciences behave…)

This collegiality becomes important later on, as the development of the field was sped up enormously by the sharing of key information between groups. This carried on well into this century, which has made AMO physics a great community to be a part of for as long as I’ve been in physics. It’s also been helpful to me as a writer, as a lot of people were very generous with their time, agreeing to Zoom interviews for these stories…

Anyway, those are some bits of stuff I wasn’t able to fit into part 1. I may have more in this vein after parts 2 and 3 get published, and hope to find a venue for even more of it down the road a bit.

If you want to see more of this whenever it drops, here’s a button:

And should you feel so moved, the comments will be open: