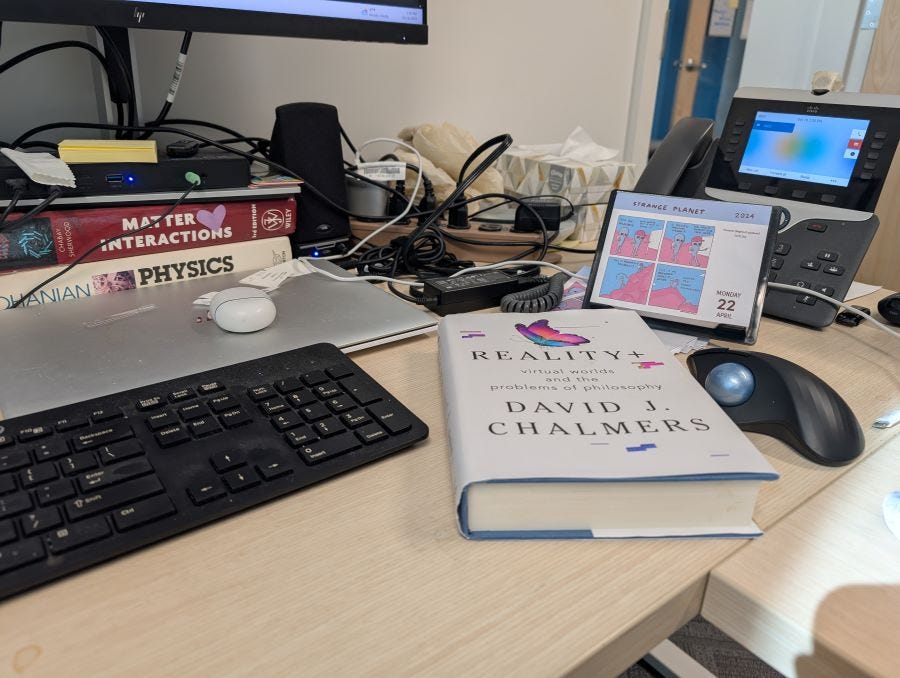

Like every other academic institution in the US, we’re getting a ton of chatter about AI these days, which is part of the motivation for an upcoming talk on campus by the philosopher David Chalmers. In conjunction with this, our new Templeton Institute for Engineering and Computer Science put together a “book club” of faculty to read and discuss Chalmers’s Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy, and in the interest of being a good liberal arts college faculty member, I signed up.

This is, as the subtitle suggests, largely a book about the “Simulation Hypothesis,” the idea that the world we perceive is not, in fact, physically real, but just a simulation being run in some deeper level of reality. In the twenty-first century, the reference everyone reaches for is The Matrix (and sequels), but as Chalmers describes this is an idea with a long history in philosophy (at least if you’re willing to tilt your head and squint a little bit to make some of the older ideas look more Matrix-like). The most fleshed out of these is probably Rene Descartes in the 1600’s fretting about whether we might be deceived by evil demons, but it reaches back to the cave allegory of Plato’s Republic around 375 BCE and the butterfly dream in the Daoist book Zhuangzi circa 300BCE.

This has picked up a lot more cachet in recent years as computer technology has improved, and that association has led it to acquire a bit of a tech-y gloss. The spicy argument these days is not just that it’s very difficult to determine whether reality is real or just a simulation, but that it is, in fact, overwhelmingly likely that we’re a simulation. The claim being that any civilization advanced enough to create simulated realities will create many more of them than there are physical realities, so statistically we’re more likely to be in one of the many subcreations than the one true physical reality. So, you know, it’s just math…

If you want to get really baroque, you can go full Boltzmann Brains: in some visions of physics, it’s conceivable that something might spontaneously pop into existence that looks like a mind perceiving a complete universe with a coherent history to it, at least for the fleeting instant before it disappears again. This is incredibly unlikely, but in an effectively infinite universe governed by quantum rules it must happen sometimes, and again, such “Boltzmann Brains” would be more numerous than actual physical brains evolved over billions of years of material reality, and therefore we’re arguably more likely to be a quantum fluctuation dreaming it has material existence than either a philosopher or a butterfly.

Chalmers’s presentation of all this is pretty good as these things go, though he suffers from both of the major tics of professional philosophers. The first being a very rigidly structured style where he first tells you what he’s going to argue, then goes through the argument, then summarizes what he just argued. This gets to be a bit much, after a while— I’m not sure every one of these arguments needs to be run through three times.

The second major philosophy-writing tic is a tendency to work through super basic and obvious stuff in laborious detail and then rush through the higher-level claims that are central to the argument, asserting that they obviously follow from the excessively detailed discussion that preceded them. I don’t always buy this, but I admit it’s an effective technique in that by the time it gets to the fast-talking bit, I usually feel ready to nod along just to pick up the pace.

This does often end up feeling like a bit of a cheat, though. In particular, as a colleague from Economics noted, a number of the arguments about the simulation hypothesis can be uncharitably summarized as “If you imagine that there’s a simulation so perfect it’s impossible to detect, then it would be impossible to know that you’re in a simulation!” Which is kind of trivially true, in the same way as “If we define a triangle as a geometric figure with three sides, every triangle you see will have exactly three sides!”

I’m trying very hard to be even-handed in my description of these arguments— you’ll have to take my word for it that I have deleted innumerable summaries that were snarkier than anything above— but I don’t find this topic all that compelling. To my mind, the most potentially interesting questions raised by the simulation hypothesis are the ones that Chalmers is quickest to wave away. The idea of an imperfect simulated universe, in which it might be possible to pick up some clue from within the simulation that would tell you that it’s a simulation, is mildly interesting to me. If nothing else, it opens the questions of what sort of clues might be detectable, and what sort of experiments you might do to uncover them.

Once you’re assuming the existence of simulations that are so perfect that they’re by definition impossible to detect, though, I kind of lose interest. If there’s nothing you can do, even in principle, to test the simulation hypothesis then it’s not a hypothesis, it’s an article of faith.

Except it’s not even religion. Probably the single most frustrating thing about the book, to me, is that there’s really never any articulation of why I should care. I’d be happy to grant even the questionable premises that lead to the conclusion that we’re overwhelmingly likely to be living in a simulation in exchange for an explanation of how this knowledge should change my life. What should I do differently in my everyday existence (or simulation thereof) once I’m convinced that we’re in a simulation that I wouldn’t’ve done prior to hearing this argument?

The answer appears to be “Nothing, really.” Admittedly, I skim-read many of the later sections (I’ve been really busy at work, and also, see previous comment about the repetitive style), but the main conclusion seems to be that since (possibly by definition) there’s no way to distinguish between physical reality and a simulation of physical reality, everything has the same status as if it were all true physical reality. In which case, none of the Big Questions of Life, the Universe, and Everything are meaningfully changed by being inside a simulation. So, you know, forty-two.

(It’s a bit like the flippant response to arguments about free will and determinism: If it turns out that you don’t have free will, what are you going to do about it?)

As always when offering negative reviews of things I will add the tepid qualifier that this is very much a Me Thing: I am an experimental scientist by training and temperament, and that very much colors my reactions. There’s clearly a significant audience for this sort of speculation, to judge both by Chalmers’s book sales and the reactions of many of my colleagues. It largely just leaves me cold, though: if there’s nothing about the argument that suggests any particular course of future action, I have a hard time working up any enthusiasm for arguing either side of the question.

Anyway, that’s kind of a squishy place to end this, so by way of apology, here’s the song that I earworm myself with every time I have to use the word “Institute”:

So, yeah, that’s a thing, or at least a simulation of a thing. If you would like more of this kind of (maybe simulated) thing, here’s a button:

And if you subscribe to a version of the simulation hypothesis that actually does suggest some change in behavior and want to try to convert me, the comments will be open:

If we were in an imperfect simulation, wouldn't we be likely to find, as we look around, a lot of fine-tuning, many hierarchy problems, and a bunch of places where deep structure does not conform to what we thought we would see from shallower structure, but rather where we have to resort to putting in extra kludgy epicycles like "inflation", "dark energy", "dark matter", and "cosmological constants"?

Or maybe we are living in a simulation. I don't see electromagnetic wavelengths, after all: I see a color wheel. How is that not living in a simulation—albeit one created by my kludgy evolved sensory pathways rather than by DesCartes's Demon?

If the world is a simulation, one should expect to see miracles. These definitely exist; the miracle of telepathy is particularly well-attested. One should also expect implausible levels of safety or dysfunctionality within the world we see, and I do think we see both.