You might not have noticed, because it slipped out with very little fanfare, but a new trailer for the forthcoming Dune movie dropped this week:

This is at least the third completed film version of Dune, following the preposterous David Lynch movie from 1984 and a Sci-Fi Channel miniseries (or were they SyFy already?) some years back. There were famously other attempts that never really got off the ground, too.

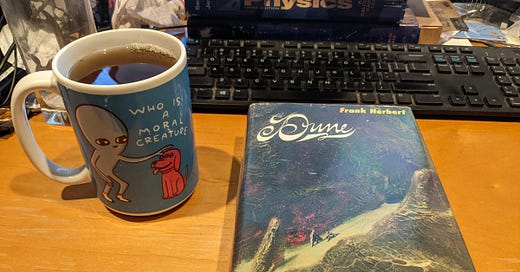

Anyway, I saw the trailer and said “Yeah, I could watch that…” Which then reminded me that I have a copy of the book, so I could read it, too. At some point in there, I also had the realization that it’s just about 40 years since I read this book.

The copy I have now is not the copy I originally read— my current copy is a hardcover that I picked up for $6.95 in a used bookstore sometime in the late 90’s (the price is written in pencil on the flyleaf). The copy I read originally was a paperback borrowed from a family friend on a trip out West in I think 1982. I’m pretty sure we returned it after that, and I got my own copies of the sequels (there were only two at the time, not the huge pile of tie-in stuff churned out after Frank Herbert’s death)— I have a weirdly vivid memory of reading Children of Dune in one of the bedrooms in my grandmother’s house on Long Island.

It was a weird experience coming back to this four decades later, because I remembered a lot about it, but in a way that reflected my pre-teen interests much more than the actual reality of the book. The plot outline is the same: the Emperor gives the noble House Atreides is given control over the planet Arrakis, which is the only source of a magical spice that’s crucial to the empire, but it’s a trick because the Emperor is conspiring with the evil House Harkonnen to move the Atreides to a place where they can be betrayed and exterminated. The Duke’s son Paul and his mother Jessica escape, and make it to the desert where they connect up with the Fremen, learn the secrets of the spice, and master the mystical powers needed to destroy the Harkonnen (with Paul killing the main villain in a knife fight) and take over the Empire. Paul, it turns out, is the Kwisatz Haderach, the product of a centuries-long program of human breeding by the Bene Gesserit order, who trained Jessica and sent her to Paul’s father. She was supposed to bear a daughter, but had a son instead, and as a result the chosen one has shown up a generation early, and turns everyone’s plans on their ear.

Oh, sorry: spoilers. But, really, it’s a book that was not remotely new when I read it forty years ago; I think the time for spoiler warnings has passed.

As I said, I remembered the outline just fine, and some of the individual scenes more clearly. What I didn’t really remember was the relative weight given to these things. In my memory, they show up at Arrakis, are betrayed very quickly, and then spend most of the book hiding in the desert learning about spice and riding sandworms and having mystical experiences, and then there’s a giant battle scene at the end. In the actual book, the move to Arrakis and the betrayal by the Harkonnen take up the first half, more or less, there’s exactly one worm-riding scene, Paul’s mystical experience takes place during a break between chapters, and the whole war of revenge takes up only about 50 pages (out of 483 in this edition). There are a bunch of knife-fighting scenes, though. (The technology and society are contrived in a way that’s clearly and deliberately designed to justify multiple scenes in which guys try to kill each other with knives. What this says about Frank Herbert, I don’t know.)

I suspect my recollection is colored to a greater degree than I realized by the David Lynch movie, which I remember seeing in the theater when it came out. Even as a teenage nerd, I knew it was kind of ridiculous, and it was a commercial flop, but it reached that weird cable-tv afterlife where it was just randomly on a lot, and achieved a kind of cult status as a result. Its pacing (as I remember it, but I’ve watched parts of it much more recently than I’ve read the book before this week) is more like what I remember.

But also, I was something like 11 years old when I read this originally, and didn’t have much patience for court intrigue and musings about prescience, so I suspect I just skim-read past a lot of the opening material to get to the knife fights and sandworms. I missed a lot of stuff in books at that time that seems really obvious if I revisit it now.

(To give an extreme example, I read Stephen Donaldson’s Thomas Covenant series at around this same time, and enjoyed them a good deal. When I discovered the rec.arts.sf.written newsgroup on Usenet in the mid-90’s, though, I was startled to see a long raging flamewar denouncing these. The reason was that there’s a rape scene early in the first book, which I had completely missed— I borrowed a copy from one of my housemates at the time, and confirmed that, yep, that’s what happened. As a pre-teen, though, that completely went over my head, as did Covenant’s moaning about it later; it just wasn’t interesting to me, so I skipped past it.)

Anyway, this is kind of a long way of saying that the actual book is much more internal than the book in my memory— more concerned with court intrigue, and fretting about how to prevent a galactic jihad than the stuff I found awesome in 1982. The awesome stuff is all there, but much more implied than described. I can see why this is such a hard book to transfer to film.

As a book, it was interesting in that it’s not exactly well-written. There’s a lot of head-hopping, where a scene that starts out tightly in the perspective of one character jumps to the perspective of another midway through, or cycles through three or four people before settling down. Some of this is remarkably clumsy, leaving the reader confused about exactly who was thinking whatever italicized thing just popped up. There’s also a lot of incredibly stilted dialogue, in a “human beings don’t talk like this” kind of way.

And yet, it’s weirdly compelling. This isn’t a short book (though not too bad by modern standards), but I powered through it pretty quickly. At times, I found myself slightly annoyed by The Pip wanting me to watch baseball games with him between dinner and bedtime, because I wanted to be reading instead. I can’t really point to any particular quality of the book that produced I can attribute that reaction to, but it worked in a way that I struggle to explain. This was not what I was expecting— I bought this copy back in the 90’s, but only got a few pages in before abandoning it, and I’ve seen a lot of people saying “Don’t bother trying to read it, it’s tedious” in discussions of the movie. It went really quickly for me, though, and while I noticed clunky bits (and let’s not talk about the world-building, okay?), they mostly sped right by.

So, in the end, I enjoyed revisiting this, and look forward to seeing what they did with the new movie. I’m not sure I can exactly recommend it to anybody who doesn’t have old memories of reading it as a (pre-)teen, but I can’t recommend against it, either, and that’s something.

I can’t say I’ll be regularly re-reading classic novels of my youth, but if this level of cultural commentary is something you’d like to receive in email, here’s a button:

If you think somebody else would appreciate it, here’s another button:

And if you’d like to reminisce about the experience of reading this or watching the Lynch movie, the comments are open.

I think the formality of the dialogue works in the sense that the Atriedes are hereditary nobility at the top of a very tall and rigid hierarchy and that the Fremen are meant to seem like an extremely formal, ritual-bound people; in both cases that makes them seem "naturally stilted", if that makes sense. There's almost no speaking characters who are "ordinary people" in any sense--say, just a regular old water-seller in the city or a spice-smuggler or a dock loader, etc.

I hear you on just skipping past some things--sooner or later I'm going to write in my re-readings about entire chunks of stuff in famous SF/fantasy works that I read when I was younger that I would just repeatedly avoid any time I read them. With Dune, I think the things that would always grab me were just the basics of the reversal-of-fortune plot--Paul's family is attacked and his father murdered; Paul proves himself to the people who takes him in; Paul hatches a plan; the plan succeeds wildly. The Chosen One mysticism surrounding that added flavor but I didn't really fully grasp the idea behind it (and Herbert didn't really explain it more fully anyway until Dune Messiah and Children of Dune anyway). Stuff like what spice was actually for, the Guild Navigators, the Sardaukar, the politics of the Landsraad, all of that didn't really sink in for me until an adult re-reading.