In one of those “Welcome to the Information Supercollider” moments (to borrow a Usenet .sig quote that was funnier when Al Gore was still a politician), we recently had a flurry of stuff about motivation in academia come through my various feeds. The oldest item was a new round of “Advice for new faculty,” to which I gave my usual answer:

Then there was this from Ash Jogalekar:

(and more importantly the tweet he’s quoting and the discussion that follows from it). And it all led up to a thoughtful Substack post from Timothy Burke:

Kind of a lot of things here, all sort of related, that bounce off each other in interesting ways. And I’m just kind of going to do a thinking-out-loud sort of thing with them in this post, and see where that leads.

I think the clearest connection is between my reheated advice and Burke’s essay about trying to figure out how to motivate students to write. That’s a lot of what my colleague was getting at, lo these many years ago: those of us who go on to become faculty had a level of intrinsic motivation in academic subjects that’s not shared with the more general population. I would procrastinate for a long time on assignments in classes outside my major, but once I sat down to actually write the thing, I was going to do as good a job as possible, because that’s just what I do. I didn’t care all that much about grades per se, but I don’t like doing things really half-assedly.

I learned even before leaving college, thanks to some group-work assignments, that this approach is not universally shared. I’ve been a professor for twenty years now, and as much as I try to keep that advice in mind, I’m still sometimes surprised at just how minimal an effort some students will put in before just giving up on a thing.

Some of that lack of motivation is a matter of not seeing the relevance. I was never fond of math classes in school, which tended to seem abstract in ways that were something between uninteresting and annoying. There’s a lot of tediously working out definitions based on edge cases that just don’t seem to mean anything. I have the same problem with philosophy.

I did a lot better in math courses that were disguised as physics classes— Fourier series in the abstract didn’t do much for me, but finding solutions to match particular patterns for waves on a string is a lot more engaging. Having something concrete to tie it to makes it a lot easier to see why I should want to do a thing. It’s like the comment somebody (I forget who) made about computer programming: The best way to learn how to program a computer is to have a problem that requires you to program a computer to solve it.

Back when we were teaching our intro classes out of the Matter and Interactions books, we used to spend a couple of labs on simulating things in VPython. When we first started this, I’d get a lot of complaints and end-of-term comments of the form “This is useless, we’re going to be engineers, not computer programmers.” I sorta-kinda got past that with two things: first, telling them very explicitly “You might not think this is relevant, but I promise you, you will be doing exactly this in [famously intimidating class taught by famously intimidating professor], so doing it now will help you then.” The more useful way to motivate it was a lab where they would first simulate and then measure the period of a mass oscillating on a real spring, and find a discrepancy between two. The discrepancy came from the fact that they didn’t include the mass of the spring in the simulation, which they could then calculate. I used that to point out that this is how science (and to some extent engineering) actually works to discover new things: you make the best model you can with the information you have, and compare it to reality, and when they diverge, you learn new things. That combination dealt with a lot of the “Why are we programming?” complaints (they were replaced with different complaints, but such is life…)

(I always half meant to write that lab up for The Physics Teacher or some such, but never got around to it, and we’ve switched back to a more traditional curriculum now, so the moment has probably passed. Alas.)

This kind of circles back around to the question raised by the Jogalekar and Kontorovich tweets above, where topics you hated in school become fascinating later. I can’t say I’ve really experienced that to the degree they talk about— my exact level of interest in other subjects has fluctuated over the years, but always around a fairly high baseline. I had specific History and English professors whose approaches I didn’t care for, but I took more classes than I strictly needed to in both areas as an undergrad because I always enjoyed them. And I still don’t care for the abstract formality of pure math more than I did as an undergrad.

I do wonder, though, how much of this has to do with motivation as opposed to what for a lack of a better term I’ll call agency. That is, I think that a big part of the reason I didn’t end up disliking the history and literature classes I took in college was that I had a considerable degree of freedom in choosing them. I had AP credits that let me skip English 101, and the general education curriculum at Williams was just a distribution requirement that could be satisfied by any course within a group of disciplines. That meant I could take relatively focused courses on topics that seemed interesting to me, rather than broader surveys hitting a bunch of different stuff with an eye toward setting up other courses.

The courses in those areas that I was least fond of were more survey-like. For example, I took an English class on medieval lit that was really an introduction to “theory,” running through a bunch of different schools of criticism in a way that made it feel very much like a bullshit game. I also took a history of Europe class that was again a bit too sweeping, moving too quickly for my taste in some parts, and lingering over stuff that felt like a waste of time.

On the other hand, two of the other history courses I took, one on Japan and the other on Vietnam, were among my favorite classes as an undergrad. And the other literature classes I took were a much better experience in large part because they maintained a tighter focus on topics I found interesting.

So, I suspect that part of what’s going on for people who hated history (or math, or physics) in school but find it fascinating later in life is that being out of school gives you a greater degree of agency, allowing you to skip the bits you find boring or distasteful. When you’re free to select the stuff that you’re really interested in, it’s not surprising that the overall experience is more enjoyable.

I think that has some lessons for things like designing GenEd curricula— I think you probably end up with a more positive student experience with a less prescriptive system that gives students agency to choose what interests them, rather than one that channels students into very specific courses. At the same time, though, there does need to be a little bit of extrinsic motivation involved, because not everything involved in actually learning a subject is fun.

Lots of people make the sort of suggestion that Kontorovich does in his tweet, that “Maybe school was the wrong place to learn [history]?” (Plug in your least favorite school subject as needed…) Some take this to an extreme, saying we should get rid of school as we know it, and just give students a radical degree of freedom to explore at will.

It’s an appealing idea in a lot of ways, but I don’t think it works. As I usually say when this comes up, the number of people who think they can be wide-ranging autodidacts is vastly larger than the number of people who can actually learn that way. This is particularly acute in the sciences, where actually learning a subject requires a degree of grinding through actual problems that is unpleasant but essential. And the number of people motivated enough to do that on their own, without somebody forcing them through it is not large.

(I count myself among that number, for the record; there are a couple of areas of physics I’ve tried to learn more about, but not got anywhere without some external pressure to force me to actually work problems. I’ve had a little more success from agreeing to teach courses in subjects I don’t know that well— knowing that you’ve got to face students in the morning concentrates the mind wonderfully, to paraphrase Samuel Johnson.)

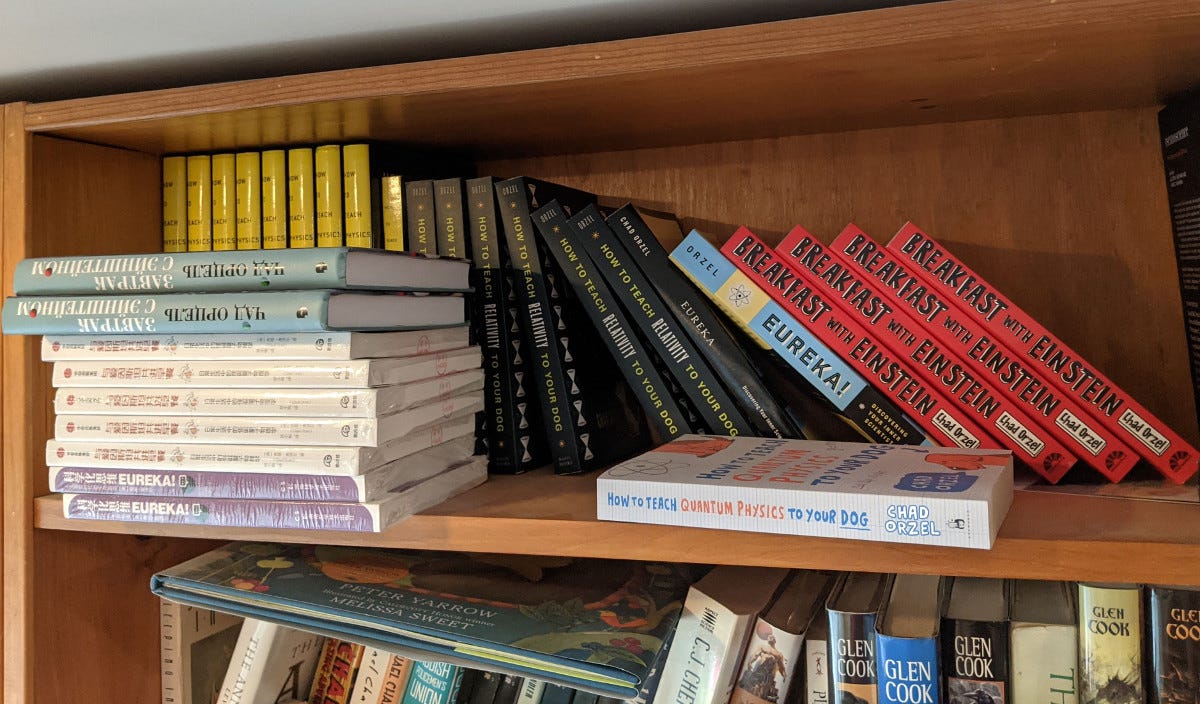

Most of what goes on when people come back to some subject later in life is not so much “learning” as “learning about.” It makes me very happy when people read my books and praise them for being enjoyable in a way that school classes were not, but my books aren’t going to teach anybody how to do physics. They’ve learned some stuff about physics, but haven’t learned physics in a way that would let them really contribute to it. (Which, I hasten to add, is perfectly fine and in fact the goal of my books.)

I suspect there’s a similar dynamic at work for people coming back to history, or math— they’re learning things about the subject, but not really learning the subject in a deep way. Unless, of course, they run across a problem that requires actual learning to solve, in which case they may find the motivation to grind through the unpleasant but necessary stuff that’s essential to real learning.

But at this point, I’ve kind of circled all the way back to the start, so I’ll stop here. There’s one other piece of Burke’s post that I want to come back to, but that’s on a separate issue, so makes sense to save for later.

If this sort of rambling and discursive thinking in type appeals to you, here’s a button:

If you think it would appeal to someone else, here’s a different button:

And if you’d like to add your own thoughts, the comments will be open.

The "I promise you" is an interesting moment in the life of any faculty member. Sometimes we are absolutely certain we're right and we are right: "I promise you that this thing we're learning doesn't seem of immediate use but it will be three steps further down the road". Sometimes we're certain we're right and we're not because something's about to change in the basic set of tools and procedures that we use right now and we don't know that any more than they do. ("I promise you that you will need to know how to operate your computer from the MS-DOS command line.") Sometimes we're trying to make an inspired guess--I keep telling my daughter that if she wants to be involved in film and media production maybe she should understand how to work in algorithmic environments since some of the actors and visuals and sound will be mediated through AIs or sophisticated programming ensembles. I may actually be wrong, plus of course I'm telling her to do something that I can't do and don't know all that much about. Sensibly she is rolling her eyes in response each time.

But I think sometimes I'm just like Geoffrey Rush's character in Shakespeare in Love, who keeps saying that somehow the production of Romeo and Juliet is going to come off and it's going to be great and when asked how he knows he just says, "I don't know. It's a mystery!" I can't even tell students why I think what we're doing is worth doing in the way we're doing it but I'm sure that it is. And I feel as if so far in my career, my percentage on this is pretty solid. It seems like this is another part of "you have to do it before you find out why you should do it"--it's about trusting someone when they say "this will be worth doing". Which is why we have to be so careful about being wrong about that in a way that could have been avoided--take a student through their paces that way to no useful or productive end one too many times and you have a person who hates education altogether.