I am not a journalist, but I’ve spent a fair amount of time being paid to write things for media companies, much of it during my long run at ScienceBlogs (RIP). This was a group that brought together a mix of professional journalists writing about science and scientists writing about their own fields, and there were a lot of arguments between the two groups. In a lot of these, I actually tended to skew toward the journalists’ side, but now I’m re-thinking that a bit. I think there are some very deep structural problems with the practice of journalism showing out in the coverage of the pandemic that need examination, but probably won’t get it.

The central (and endless) journalists vs. scientists argument centered around a collection of stuff that might conveniently be shorthanded as “hype.” Scientists tend to get aggrieved about journalists stripping away the caveats and qualifications and presenting preliminary or marginal results in a way that makes them seem more definitive than they actually are. This problem is most acute in the biomedical field, where the historical standards for significance tended to be a bit low, leading to the well-known phenomenon of endless strings of contradictory reports about diet, each presented with the same breathless excitement: Chocolate is good for you! Nobody should eat cheese! Red wine lowers the risk of heart attacks! And on, and on, and on…

I tended to lean toward the journalists’ side on this, just from the perspective of telling stories. Yes, there’s some oversimplification going on in these, but a lot of the time, the concerns are pretty minor. Not every simplification is a “dumbing down,” done to make scientists look bad; most of them are necessary to make the story flow well for a person who doesn’t have a Ph.D. in the relevant subject. On a few occasions I phrased this as “scientists need to get over themselves.”

(For balance, I also had a “Journalists need to get over themselves,” which related to their insistence on an adversarial model in which it would be unethical to let scientists read over drafts to check for accuracy. That’s just as farcical as the idea that journalists are out to “get” researchers—a weekly news squib about recent results is not the Watergate investigation, it’s okay to check copy with the subjects of the story.)

I’m swinging more toward the scientists’ side of this, though, after the collective response of journalists across a wide range of media covering the Covid pandemic, particularly the post-vaccine phase. This has been, to put it mildly, a catastrophic shitshow, and the reason why is embedded in those same norms of story telling.

I’ll outsource my data collection here to Carl Bergstrom, who highlights a bunch of terrible headlines in this Twitter thread:

These mostly turn on the “leaked” CDC slides about the Covid spike after the Fourth of July week in Provincetown, and what that means for vaccinated people. This was apparently a key part of the case for re-imposing mask mandates, but the interpretation has been widely challenged by people with relevant expertise in medical research and public health. Leading to Bergstrom’s rant.

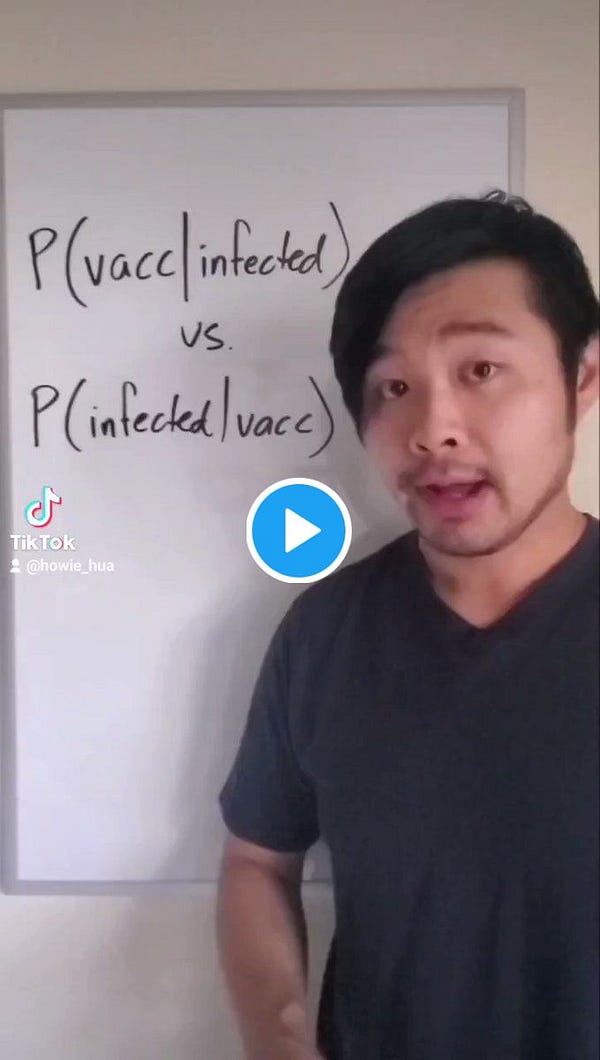

The charitable interpretation of this is that it stems from innumeracy: journalists aren’t understanding the difference between the probability of infected people being vaccinated and the probability of vaccinated people being infected, and that sort of thing. This has produced some good stuff, like this very clear video about the difference in the probabilities:

The less charitable interpretation is the one Bergstrom puts forth in his thread, namely that this is cynical clickbait on the part of journalists. They’re going with headlines that are actively irresponsible because they need people to click on the stories to get ad revenue.

I don’t think it’s consciously cynical on the part of publishers and editors and headline writers— that’s an overly dramatic interpretation, just like “journalists are trying to make me look bad by overhyping results.” I think the problem is deeper and more insidious than that— it’s baked into the deeply ingrained professional norms of journalism. This isn’t just a matter of bad headlines, it’s about the whole way that stories are chosen and written.

The fundamental problem here is as old as the profession of journalism. We get high-profile stories about breakthrough infections in vaccinated people because that’s the kind of story that reporters are trained from birth to recognize as interesting and important, while the much greater toll of infections among the unvaccinated is just a constant background of misery at this point. The unvaccinated who get sick are a bunch of dogs biting men, but a breakthrough infection is a man biting a dog, and that runs on the front page.

The same thing happens within the stories: as innumerable people have noted, the stories about the Provincetown study (and all the other flawed reports) generally contain the actual correct information— that the outbreak was relatively small and quickly contained thanks to the much lower rate of infections among the vaccinated. It’s just buried way down in the twelfth paragraph, after a bunch of more alarming-sounding stuff at the top. But again, this isn’t consciously cynical, it’s just the inverted pyramid format that reporters are taught to use when writing stories. You put the eye-catching stuff at the top (vaccinated people can transmit the virus!), and the boring details (vaccinated people are much less likely to get infected!) toward the end.

This isn’t a social-media, clickbait-driven problem. This is print newspaper, Strunk and White kind of stuff. Nobody is cynically thinking “We need to hype this up to get clicks,” they’re just drawing on deep reflexes and professional norms around the way stories are chosen and presented to the audience.

As I said in my cynical retweet of Bergstrom’s thread above, I think there’s a parallel here to the debacles of the 2016 election, when media flocked to the Trump campaign and overhyped the Clinton email pseudo-scandal for the same sorts of reasons. I don’t think that reporters (outside of a few pundits) genuinely had it in for Hilary Clinton, I just think their professional norms pushed them in a direction that worked to her detriment and Trump’s benefit, which had disastrous consequences. Which was pretty much the defense offered when people complained about the media’s role in the election outcome: that they didn’t do anything that wasn’t standard practice for the industry.

The problem then, and the problem now is exactly that the standard practices of the industry are easily gamed. And that was never really openly reckoned with in the case of the 2016 election— the media did eventually adjust to Trump, but slowly and quietly, in a way that didn’t require anybody to accept any responsibility for anything. I suspect something very similar is going to happen here.

Unfortunately, the problem I think we have here is both structural and very deep, in a way that makes it hard to see a clear solution. The inverted pyramid structure and the novelty bias aren’t just a creation of journalism schools, they’re tapping into some deep instincts about how we as humans construct and process stories— that’s why they work. As we’re seeing now, though, those structures and practices can run directly counter to the (ostensible) greater goal of properly informing the public, which can have deadly consequences. I think that’s something that people in the industry need to think about in a serious way, before the next big crisis rolls around.

If you were brought in by my clickbait headline, but would like to receive this sort of thing in your email, here’s a button for you to click:

If you think somebody else in your life ought to read this, here’s a different button:

If you’d just like to yell at me in my own space, the comments will be open.

I think you are overly generous to the journalists. It is completely cynical on their part. They act like used car saleman.