Mid-March is close to the season when graduate and undergraduate admissions decisions get made, and toward the end of the faculty hiring cycle. Both of these lead to a lot of discussion of diversity issues about who’s getting hired/admitted and how things are or are not changing.

The resulting arguments have a tendency to be conducted via a mish-mash of percentage statistics and absolute numbers, which can tend to confuse the issue as much as clarify it. Having seen a few things on Twitter in the last week or two that seemed a bit muddled, I spent a little while poking around the AIP Statistical Research Center looking specifically at the stats regarding women in physics faculty roles, and having put that work in, I thought it might be worth sharing the data here.

One of the most important figures for putting all other discussions in context is the overall scale of the profession. According to the stats in the table above, there are just over 10,000 full-time-equivalent faculty positions in physics in the US, about a third of them at institutions that only grant BA/BS degrees, and most of the rest at Ph.D.-granting institutions. According to AIP, women make up 19% of the total faculty, so a bit more than 1900 of those FTE faculty. About 80% of the overall faculty are in tenure-track lines (a bit higher at doctoral institutions, a bit lower at the bachelor’s level); the gender breakdown varies by rank, with the fraction of women dropping as you move up, from about 25% women at the Assistant Professor rank to 12% at Full Professor.

The next critical factor to understand is the state of the job market. According to the AIP stats, their most recent year of data involved about 369 new hires in the tenure-track level, plus another 65 non-tenured but permanent positions, and 137 temporary jobs:

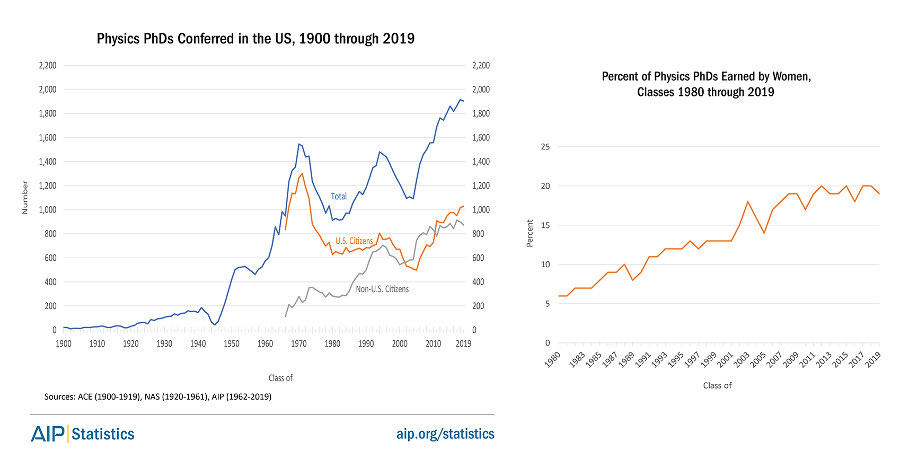

The next important question to ask concerns the numbers in the pool of people who could take those jobs. I’m going to awkwardly composite together a couple of figures for this one:

The overall number of Ph.D.s in physics has risen steeply in recent years, from around 1500 circa 2010 to around 1900 in 2019, while the percentage of women earning those degrees has remained flat at just under 20%. That means there were somewhere around 380 women in the Ph.D. class of 2019 (up from 300 a decade ago). By coincidence, this is pretty close to the total number of tenure-track faculty openings.

And that gives you a sense of why effecting change here is slow. To put it in round numbers so extra digits don’t obscure things, you’ve got about 10,000 total faculty in the country, and in any given year can replace only around 400 of them. If you hired all of the women granted Ph.D.’s in any one of the recent cohorts, and only those women, the biggest shift you could possibly get in the faculty gender balance is moving from about 19% to about 23% women (assuming that these are just replacements, not an increase in the overall number, that none of the existing faculty who get replaced were women, and that none of the new Ph.D.’s would prefer a career outside of academia).

The actual stats for recent hires make for a smaller change: about 27% of new hires were women. That’s a higher percentage than in the Ph.D. cohort, and a higher percentage than in the existing faculty, but it would only shift the total pool from 19% women to a hair over 20% (again, assuming the existing faculty who get replaced are all male).

You could go through and do a similar analysis for racial diversity; AIP has similar reports on that (the overall picture is similar, but all the fractions are smaller). But this should suffice to give a sense of the important scales here.

I’m trying to keep this post as a “just the facts” kind of deal, without making any particular arguments about what ought to be done, here; that will wait for a subsequent post. If you’d like to see that as soon as it arrives, or know somebody who ought to see this, here are the usual buttons:

If you’ve got opinions on these figures, or suggestions to make, the comments will be open.

Feels as if the figure that matters here is not "how slow progress is in hiring because only 400 jobs a year are open" but "the number of women pursuing physics doctorates is flat". Meaning, what is making change very slow is that women are a small percentage of all people pursuing the degree and that percentage is not growing. If the number of students in graduate programs was suddenly a 50-50 ratio, unless there was active discrimination in hiring, retention and tenure, a given discipline would slowly but surely approach 50-50 in faculty. Whereas if one gender is only 20% of the people receiving doctorates, there's no way to achieve gender parity in faculty without extraordinary coordinated measures in hiring. This is why so many people thinking about DEI issues in particular disciplines focus on changing the "pipeline" first and foremost.

As far as that goes, the problem obvious extends back even into high school, but a key number is "what's the gender (or race etc.) distribution in introductory undergraduate classes" and then to track how that distribution changes for majors over time. If you see a point where the gender distribution changes dramatically and it's fairly late in the course of study, it means the most important problem to solve is in undergraduate education, and it means there is something that faculty are doing (or not doing) that is playing a fairly direct role in disfavoring the group who start to disappear from the major. If on the other hand you start off in year 1 with a bad gender imbalance, it means the most serious problem is rooted in something that precedes college. If you have a discipline where students finish with a fairly even gender balance and then suddenly one gender disappears from the "pipeline" and never applies to graduate school, the problem is downstream from college and needs to be fixed there.